Queer Palimpsests: Rewriting Medieval Art History

RAP Graduate Student Symposium

April 11, 2025

The Research and Academic Program (RAP) at the Clark Art Institute invited graduate students for a one-day symposium, “Queer Palimpsests: Rewriting Medieval Art History,” held at the Clark in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

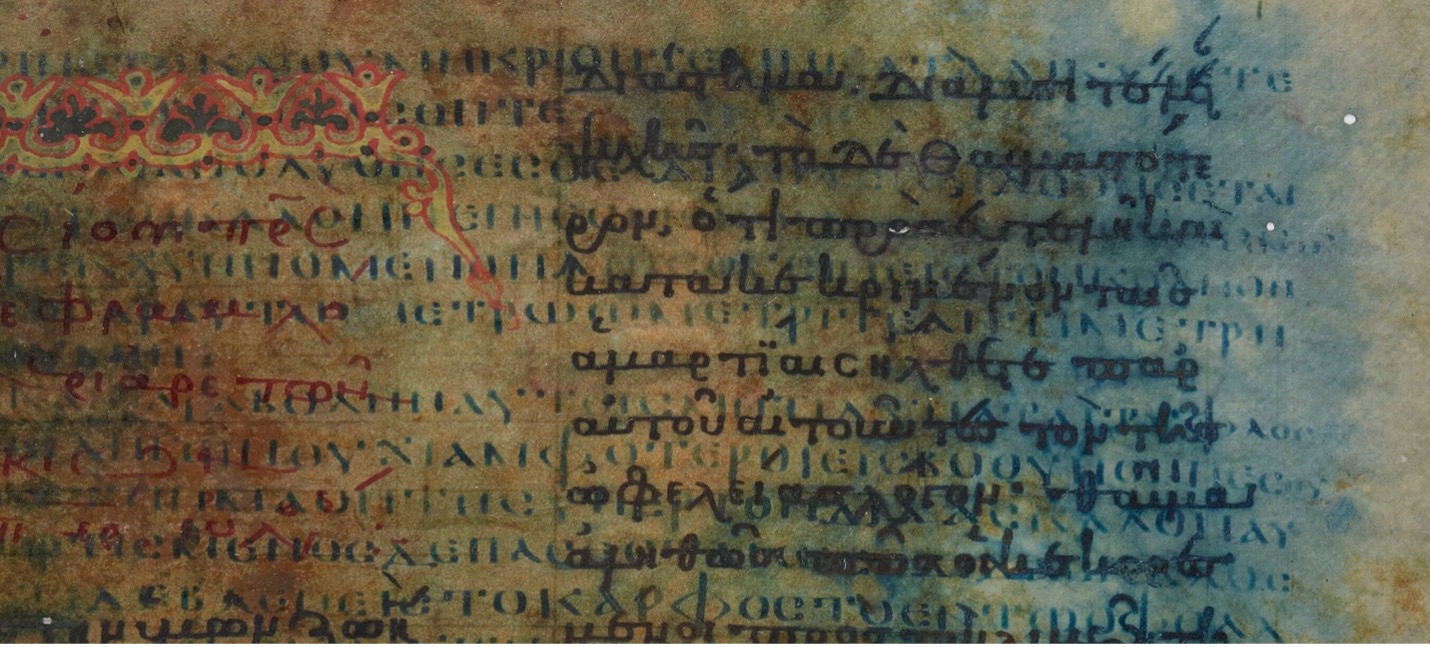

In the Middle Ages, palimpsests were parchments whose original text or imagery was effaced in order to reuse their valuable substrate. A transliteration of the Greek word παλίμψηστος (palimpsestos), palimpsest literally means “scraped again,” denoting the process of scraping or rubbing a piece of parchment. Sometimes this repurposing was achieved hastily, leaving behind traces of the original text or image. Beyond its literal meaning, today the term has gained other metaphorical resonances. Collapsing iterations of writing and/or image on the same page, palimpsests evoke questions of temporality, textuality, touch, labor, use, and use value. Queerness has been theorized to—like a palimpsest—decontextualize and reemploy objects.

The theme Queer Palimpsests evokes this history and is meant to be capacious. Scholars of medievalism might point to the queerness of refashioning the medieval past for the purposes of a given present moment, while medieval manuscript specialists might find queer case studies of palimpsests or imagistic effacement. We also welcomed papers that consider historiography and methodology, treating academic discourse over the decades as itself a kind of palimpsestic process. To what extent does the term “palimpsest” comment on the practice of queer medieval art history itself?

The symposium was convened by Luke Williamson (Williams Graduate Program in the History of Art, ’25) and organized by the Research and Academic Program.

The event concluded with a public keynote delivered by Karl Whittington (Professor of Art History at The Ohio State University) on "Queer Making: Artists and Desire in Medieval Europe."

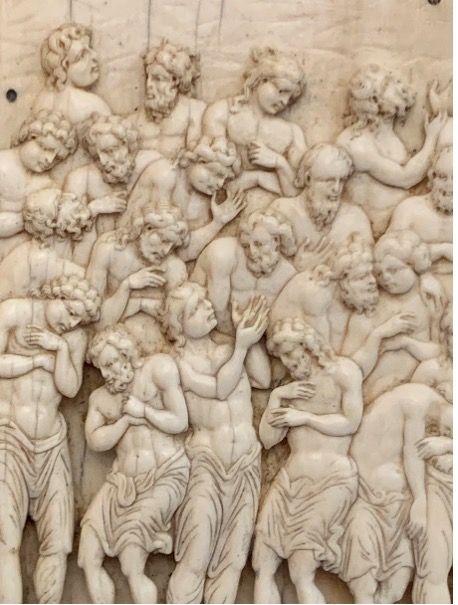

What role does desire play in the making of art objects? Art historians typically answer this question with reference to historical evidence about an artist’s sexual identity, personality, and relationships, or with reference to particular kinds of imagery in works of art. But how do we think about desire in the case of anonymous artists or in works whose subject matter is mainstream? We know little about the lives and personalities of the makers of most works of art in Europe in the Middle Ages, but this should not hold us back from thinking about their embodied experience. This talk argues that we can “queer” the works of anonymous historical makers by thinking not about their identities or about the subject matter of their artworks but rather about their embodied experiences working with materials. Through considering issues of touch, pressure and gesture across materials such as wood, stone, ivory, wax, cloth, and metal, Whittington argues for an erotics of artisanal labor, in which the actions of hand, body, and breath interact in intimate ways with materials. Combining historical evidence with more speculative description, this talk broadens our understanding of the motivations and experiences of premodern artists.

Images: Palimpsest with texts from the 5th and 12th centuries. Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF), Département des Manuscrits. Grec 9 (Codex Ephræmi Syri rescriptus) fol 1r; Forty Martyrs of Sebaste (detail), Ivory, Constantinople, late 10th Century. Bode Museum, Berlin.