Arabesque

December 14, 2019–Maarch 22, 2020

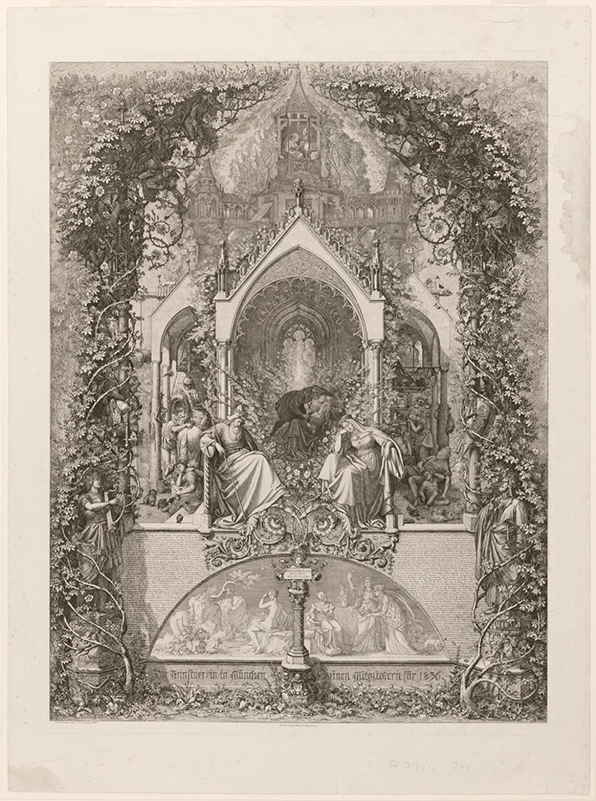

Eugen Napoleon Neureuther

Little Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty)

1836

Etching on steel

Image: 26 1/4 × 19 3/4 in.

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

The Muriel and Philip Berman Gift, acquired from the John S. Phillips bequest of 1876 to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, with funds contributed by Muriel and Philip Berman, gifts (by exchange) of Lisa Norris Elkins, Bryant W. Langston, Samuel S. White 3rd and Vera White, with additional funds contributed by John Howard McFadden, Jr., Thomas Skelton Harrison, and the Philip H. and A.S.W. Rosenbach Foundation, 1985

1985-52-2324

Arabesque in Literature

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the German critic, poet, and philosopher Friedrich Schlegel used the term “arabesque” to express his literary concept of Romantic irony. Romantic irony described texts that displayed a playful seriousness, drawing upon the romantic idealism of the past. Their authors self-consciously adopted recognizable romantic tropes—anything from medieval chivalric manners to eighteenth-century notions of the picturesque and the sublime—to ironic effect. Texts that displayed a sense of romantic irony were not to be taken at face value, but neither did they mean the exact opposite of what they said. For Schlegel, the back-and-forth curve of the arabesque perfectly encapsulated literary forms that expressed this playfully ambiguous union of opposites.

The arabesque in literature could also express a sense of ambiguity that had an undertone of the fantastical or mysterious. A signal example from American literature is Edgar Allan Poe’s 1840 collection of stories Tales of the Grotesque and the Arabesque. Those two visual words, Poe claimed in his preface, illustrated “the prevalent tenor of the tales here published.” That “prevalent tenor” was one of indeterminacy, in which the logic of the everyday dissolved into something bizarre, dreamlike, and sometimes terrifying. Poe imagined something analogous to his fantastical narratives in the visual form of the arabesque. It could appear to meander without any definite trajectory. Its cursive could even look like maddeningly unreadable script.

On the page, a drawn arabesque could communicate a relationship between text and image that was both fantastical and playful, a strong contrast with the hard rectangular borders that typically emphasized the separation of word from image. The meandering form of the arabesque, which looped first this way, then that, evoked a freedom from constraint, implying that the boundaries between the two modes of expression were not quite so fixed. The arabesques that adorn the two first plates from Peter Cornelius’s suite, Twelve Illustrations to Goethe’s Faust, are figures for the imagination, allowing viewers to toggle between the errant realm of fantasy and the inexorable narrative of the well-known Faust legend.