COLLECTIONS ACTIVITY

The Clark Art Institute continues to build and shape its collection to realize more fully and effectively its mission. The Clark’s decisions regarding the acquisition and deaccessioning of works in its collection are guided by a collection management policy that carefully adheres to the professional standards set forth by both the Association of Art Museum Directors and the American Association of Museums.

RECENT ACQUISITIONS

Early Photographs of and by Black Americans

Recent important gifts from Frank and Katherine Martucci are advancing efforts at the Clark to bring a wider range of stories to light—through exhibitions, collection displays, and public programming. Recognizing that images of and/or by Black Americans are far too rare in the museum’s current holdings, the Clark profoundly appreciates the Martuccis’ generosity and vision. This growing set of works, upon which the Clark will continue to build, enables the Institute to present authentic depictions of and by Black Americans from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period unfortunately often characterized by stereotyped and derogatory imagery. The Clark will continue to promote the acquisition of depictions of Black American life while seeking meaningful ways to display, interpret, and contextualize these works as part of its overall mission.

Unknown photographer, Untitled (Two Gentlemen), ambrotype. Clark Art Institute, Gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2020.8

Edward J. Souby, Portrait of a Man, c. 1879–91, paper print mounted on card. Clark Art Institute, Gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021.4.6

In the decades leading up to and following the American Civil War, caricatured or pejorative imagery of Black Americans was rampant in both the North and South, regardless of attitudes toward emancipation and abolition. Jasmine Cobb, author of Picture Freedom, has pointed out that “image makers for and against abolition organized a visual culture in which viewers rarely, if ever, saw images of free Blacks behaving as US citizens.”[1] The preponderance of racial and racist stereotyping in nineteenth-century imagery calls out for correction so that Black Americans’ roles as contributing members of society can be highlighted.

Photography had a major role to play in the democratization of portraiture, allowing artists and sitters who too often had been excluded from traditional artistic endeavors to have a hand in shaping their own portrayal. Ambrotypes, which produced a single inexpensive print that could be made while the sitter waited, reached their greatest popularity during the Civil War years and offered Black Americans new opportunities for self-representation. In this image, two gentlemen, perhaps two brothers or a father and son, are dressed in formal clothing and look at the camera with confident gazes. Like many ambrotypes of the period, this one is enclosed in a metal frame and velvet-lined carrying case for its protection, underscoring its preciousness. This ambrotype was the Martucci’s first gift of Black American photography, in 2020.

After the gift of that first ambrotype, which broke new ground in the Clark’s collection, the Martuccis’ gift continued with a series of additional photographs. These works vividly document the tradition of self-representation among nineteenth-century Black Americans. As Cobb has remarked, early photographs depict Black people as “self-possessed, free from slavery.” They involve “the gaze of the free Black photographer shot through the lens of the camera, the gaze of the free Black person seated as subject looking through the other side.”[2]

The image of a young African American man holding a cane in one hand and a bowler hat in the other was taken by the photographer Edward J. Souby, whose studio was at 118 Canal Street in New Orleans. An inscription on the back indicates that the sitter was seventeen years old at the time of the portrait. Just as important as the sitter’s exact identity, which may never be determined with certainty, is his self-presentation—his posture, dress, and mode of addressing the camera, all enhanced by chosen background and studio props.

[1] Jasmine Nichole Cobb, Picture Freedom: Remaking Black Visuality in the Early Nineteenth Century (New York: NYU Press, 2015), 154.

[2] Cobb, Picture Freedom, 3.

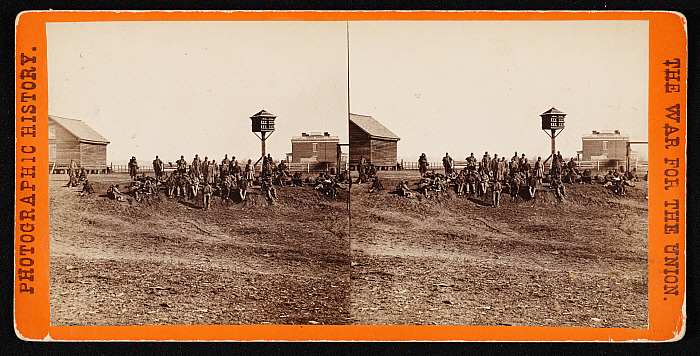

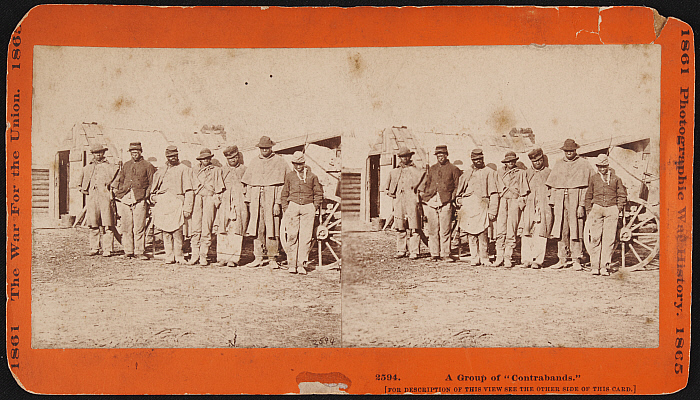

Unknown photographer, Convalescent Soldiers Resting after a March, at Aiken’s Landing, James River, Va., c. 1861–65, printed later, albumen silver print. Clark Art Institute, Gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021.4.3.

Mathew Brady Studio, Bermuda Hundred, Va. African American Teamsters Near the Signal Tower, 1864, printed later, photographic print from glass negative on mount. Clark Art Institute, Gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021.4.4.

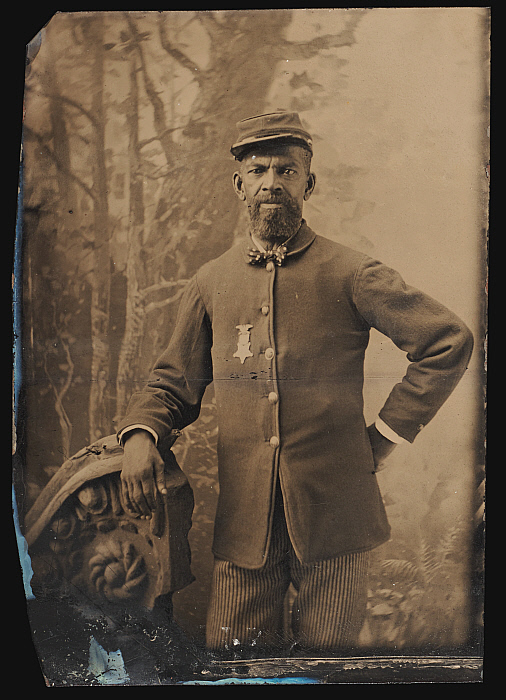

Unknown photographer, Portrait of a Civil War Veteran Wearing a Grand Army of the Republic Medal, c. 1866–70, tintype. Clark Art Institute, Gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021.4.2

Parish & Smith, 29th Company, 8th Battalion: 166 Depot Brigade, Camp Lewis, WA , 1918, Photograph mounted on card. Clark Art Institute, Gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021.4.5.

The contributions of Black Americans in military service have often gone underrepresented in the historical record. In 1861, at the start of the Civil War, Black Americans were prohibited from serving despite their eagerness to fight for a cause so interwoven with their fate. Frederick Douglass, who self-emancipated and become an abolitionist leader, wrote: “We are ready and would go, counting ourselves happy in being permitted to serve and suffer for the cause of freedom and free institutions.” At the urging of Douglass and others, Abraham Lincoln in 1862 issued the Emancipation Proclamation officially allowing freed Black men to enlist in the armed services. Nearly 200,000 answered the call, but they served in segregated regiments and were denied equal pay, protection, promotions, and treatment.

Black Americans who contributed to the war effort are featured in two stereographic pairs donated by the Martuccis. Stereographs are double images that give a combined three-dimensional effect when viewed through a stereoscope. The first pair shows Black soldiers at Aiken’s Landing, located on the north bank of the James River about ten miles from Richmond, Virginia. Aiken’s Landing served as a frequent transfer point for newly released Confederate and Federal prisoners, many of whom were emaciated and in need of rest before they could continue their journey. The second stereographic pair, originally titled “A Group of Contrabands,” employs a term then given to the Black Americans who, having fled slavery and come into Union lines, were routinely hired by the US government as teamsters and laborers.

The medal worn by the sitter in the tintype portrait identifies him as a member of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a fraternal organization for veterans who had fought in the Civil War on the Union side. Unlike most other fraternal and patriotic societies of the nineteenth century, it was racially integrated. In its work as a political advocacy group, the GAR pressed for the creation of Decoration Day (now known as Memorial Day) and supported voting rights for Black veterans. The pictured individual also wears a kepi (visored cap), 5-button military coat, and patterned bowtie.

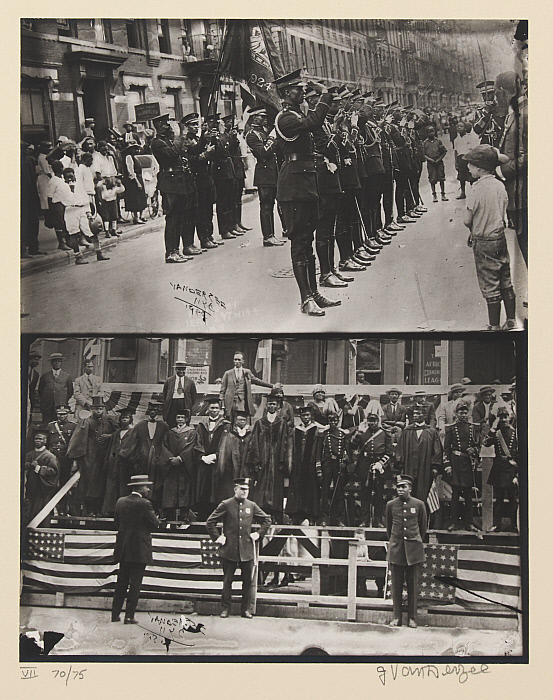

In World War I, injustices and discrimination against Black soldiers continued. Although depot brigades and some other functions were integrated—as seen in the 1918 group photograph taken at Camp Lewis, Washington—it was not until 1948 that the military was fully desegregated by executive order of President Harry S. Truman.

James Van Der Zee, Wedding Day, Harlem, 1926, printed 1974, Gelatin silver print. Gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021. The Clark Art Institute, 2021.5.

James Van Der Zee, Marcus Garvey and Garvey Militia, Harlem, 1924, printed 1975, Gelatin silver print. Gift of Frank and Katherine Martucci, 2021. The Clark Art Institute, 2021.11.2.

Born in Lenox, Massachusetts, James Van Der Zee (1886–1983) is best known for his portraits of the African American middle class and his scenes of everyday life during the Harlem Renaissance, of which he was a leading figure. A primarily self-taught photographer, Van Der Zee worked as a darkroom assistant, then as a photographer, in a portrait studio in Newark, New Jersey, that had a mostly white clientele. When he moved to New York City in 1915 or 1916, Van Der Zee opened his own studio on West 135th Street, which marked the launch of his career as the most successful photographer in Harlem. His subjects included activist Marcus Garvey, dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and poet Countee Cullen. But it was not only his notable portraits that captured this vital cultural epoch; Van Der Zee also photographed the occasions and celebrations of ordinary people.

With the Martuccis’ formative gifts, several of which appeared in the spring 2022 exhibition As They Saw It: Artists Witnessing War, the Clark is poised to continue acquiring and displaying images that give fuller representation to the histories and contributions of Black Americans.