Arabesque

December 14, 2019–March 22, 2020

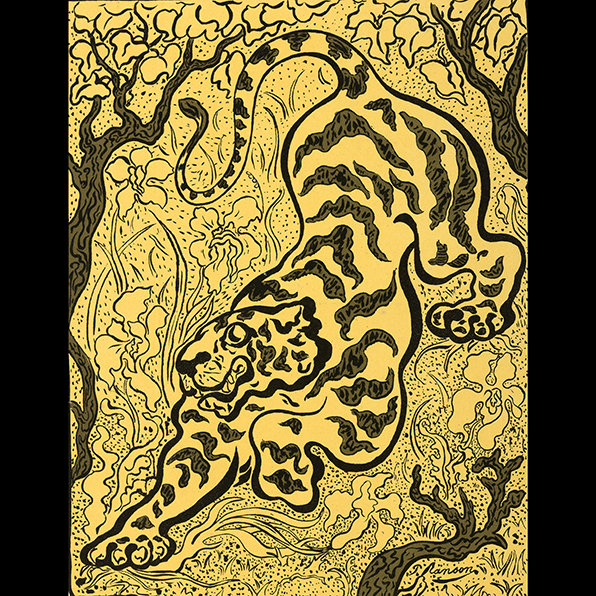

Paul Elie Ranson

Tiger in the Jungle

c. 1893

Color lithograph on paper

14 7/16 x 11 3/16 in.

Museum purchase, Joseph O. Eaton Fund.

Williams College Museum of Art

57.33

About the Exhibition

Like the notes of a melody or a dancer’s movements, the arabesque line in a painting or poster unfolds in a freely evolving form that is as distinctive as it is variable. Based on stylized motifs of vegetal ornament such as intertwining tendrils and leaves, the arabesque line has long been admired for its decorative qualities and its extraordinary flexibility. Without constraints or a predetermined path, it wanders and swirls in open-ended, unpredictable ways.

The term “arabesque,” a French word derived from the Italian “arabesco,” speaks to the motif’s origins in the art and architecture of the Arab world. Western fascination with arabesque design, though complicated by misreadings of its Islamic and pre-Islamic sources, helped make it integral to European art. For a long period, arabesque was consigned to the border, used as a visually pleasing framing device. With its exceptional freedom and flexibility, however, the arabesque line gradually evolved into an independent driver of pictorial innovation.

During the nineteenth century, a wide array of European artists explored the creative potential of arabesque across various media. The examples gathered here encompass a remarkably diverse set of styles. The exhibition begins with the highly ornate, detailed, fanciful compositions of the German Romantics, with strong links to literary sources; then moves on to historicist adaptations and interpretations directly inspired by Islamic designs, which travelers like Owen Jones helped make available to Western viewers; and concludes with the pictorial experiments of Nabi and Art Nouveau artists, powerfully informed by contemporary developments in music and dance. Bridging cultures and media, arabesque did not settle into a single form or style but rather burst open the aesthetic possibilities available to artists of this period, tracing a winding path from decorative border to overall principle of design.