MARCH 5–OCTOBER 1, 2017

Image Gallery

GERRIT DOU

DUTCH, 1613–1675

GIRL AT A WINDOW

c. 1655

Oil on panel (detail)

The Clark, 1955.716

Leaning over a stone window ledge with her hand braced upon its edge, Gerrit Dou’s young kitchen maid focuses her attention beyond the picture plane. Light from the upper left creates warm highlights on the silver flagon and angled shadows that fall against the stone. With her flushed cheeks and revealing neckline, the young woman charms and seduces as she seemingly enters into the viewer’s space. This clever pictorial invention—a kind of trompe l’oeil (fool the eye) effect—creates the deceptive appearance of reality. Artists and collectors in Leiden greatly admired Dou for his brilliant mastery of the brush, as well as his ability to reinterpret traditional subjects like the kitchen maid into a display of playful domesticity.

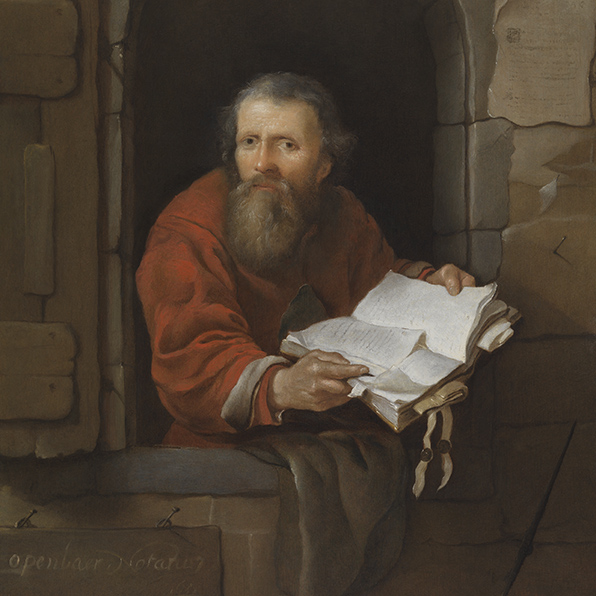

GABRIEL METSU

DUTCH, 1629–1667

PUBLIC NOTARY

c. 1653

Oil on panel (detail)

The Leiden Collection, New York

Gabriel Metsu’s bearded, elderly man stands behind a stone window ledge and holds a book open before the viewer. The sign nailed just below the wooden shutter—openbaar Notaris—identifies him as a public notary. The man’s direct gaze and extended gesture give him a striking immediacy as if he is offering his services to the viewer. Metsu left his native Leiden shortly after executing this painting, but he continued to respond to the themes and motifs popularized by Gerrit Dou, adopting fluid, broad brushwork to convey a similar sense of painterly illusion.

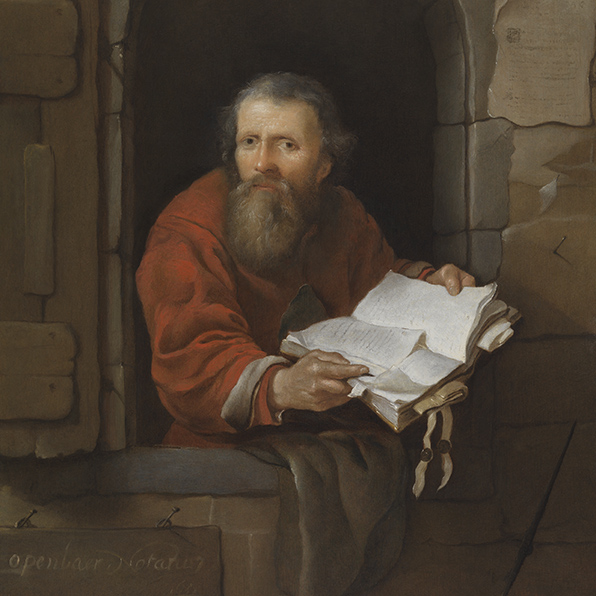

GABRIEL METSU

DUTCH, 1629–1667

WOMAN READING A BOOK BY A WINDOW

c. 1653–54

Oil on canvas (detail)

The Leiden Collection, New York

A woman dressed in a red velvet robe, white blouse, and plumed beret sits before an open window reading a large book with worn edges. Her elaborate, antique-style clothing does not belong to the seventeenth century, but instead indicates that Gabriel Metsu sought to convey a more general impression of the scholarly tradition. To do so, he likely referred to the Dutch edition of Cesare Ripa’s book of emblems, the Iconologia, in which the personification of understanding (or knowledge) takes the form of a female scholar with an open book. The clever inclusion of Metsu’s signature on a piece of paper tucked into the window frame heightens the realism of the scene—the signature is part of the depicted world, and therefore “in” the painting rather than “on” the painted surface.

GABRIEL METSU

DUTCH, 1629–1667

WOMAN DRAWING WINE FROM A BARREL

1656–58

Oil on canvas (detail)

The Leiden Collection, New York

This dimly lit room reveals a young man and a woman retrieving wine from a barrel. Various still-life objects lie in the foreground, including a heaping plate of fish being eyed by a cat. The amorous associations of wine are complemented by Gabriel Metsu’s depiction of different forms of warm illumination. The candle and lantern in the foreground flicker delicately over the figures’ faces, while an old woman holds a small light in a back room. Her presence expands the depicted space, while creating a contrast with the pair of youths in the foreground.

DOMENICUS VAN TOL

DUTCH, C. 1635–1676

BOY WITH A MOUSETRAP BY CANDLELIGHT

c. 1664–65

Oil on panel (detail)

The Leiden Collection, New York

Holding a mousetrap in one hand and a flickering candle in the other, a young boy looks knowingly out at the viewer from this darkened wine cellar. A still life of various objects—a wine barrel, milk jug, and head of cabbage—sits close to the foreground in this fictive arched frame. This lively image, painted by Domenicus van Tol, a pupil and nephew of Gerrit Dou, may have held a moralizing message. Mousetraps often had associations with the entrapment of love, while the dead fowl hanging on the wall above carried erotic connotations because of the double meaning of the Dutch word vogelen (to bird, or to copulate). Whether or not the boy warns us of the dangers of love, his softly illuminated face and gentle smile draw us in to this deceptively deep space.

JACOB VAN TOORENVLIET

DUTCH, 1640–1719

ALCHEMIST

c. 1684

Oil on copper (detail)

The Leiden Collection, New York

Two men surrounded by a clutter of scientific tools, minerals, and papers exchange reactions over a block of stone that has emerged from the oven behind them. They are engaged in the practice of alchemy, a pseudoscientific profession that sought to turn base metals into gold. By this time, people doubted the plausibility of alchemy, and many artists depicted it mockingly, but Jacob van Toorenvliet rendered the subject with dignity. The meticulous handling of various materials and textures—from the soft fur trim on the man’s coat and hat to the torn and well-used pages of the book—reinforces his careful attention to the scene and the emphasis on both the practical and intellectual aspects of the activity.

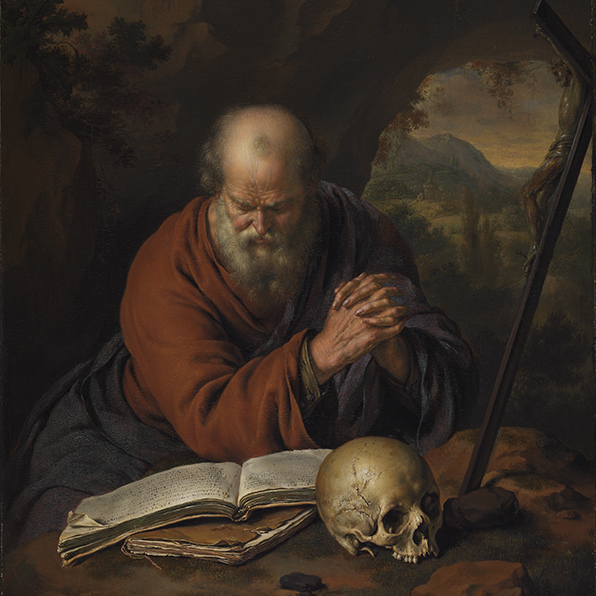

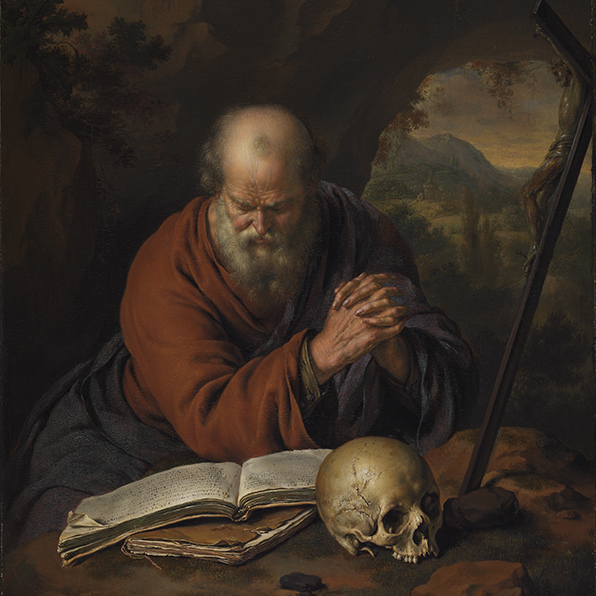

WILLEM VAN MIERIS

DUTCH, 1662–1747

HERMIT PRAYING IN THE WILDERNESS

1707

Oil on panel (detail)

The Leiden Collection, New York

Willem van Mieris’s depiction of an elderly hermit praying in a remote cave, entirely removed from the world, reflects the importance of the contemplative life. Hands clasped and eyes downcast on the open pages of a book, his concentration is palpable. The skull and sculpted crucifix serve as reminders of mortality and salvation. Van Mieris’s technique is incredibly precise, evident in the articulation of single strands of curled hair on the man’s beard and the dirt beneath his fingernails. The artist continued to produce paintings in the fijnschilder technique well into the eighteenth century, demonstrating the longevity of this tradition and its continued popularity among a later generation of collectors.