December 14, 2019–FEBRUARY 13, 2020

ARABESQUE IN DANCE

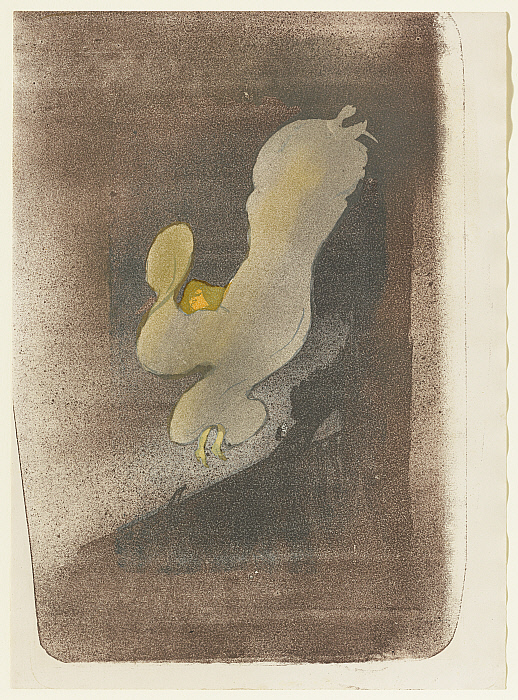

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1864–1901), Miss Loïe Fuller, 1893. Lithograph printed in blue-gray, brown-aubergine, and yellow, touched with gold and silver powder on cream wove paper, 14 3/8 x 10 1/16 in. Clark Art Institute, 1962.105

The term arabesque in classical ballet refers to a specific pose, in which the dancer’s weight is supported by one leg while the other leg is held backward in the air. This highly specific meaning was first used by the Italian dancing master Carlo Blasis in an 1820 treatise on dance. It came to include several variations on the basic position that form part of the repertoire of both classical ballet and modern dance. According to Blasis, the attitude of the body that it described could be seen in relief carvings and paintings from Classical antiquity, as well as in Raphael’s frescoes. However, the term had been applied to dance before Blasis assigned his highly specific meaning to it. He wrote that previously “arabesque” had described certain configurations of dancers that echoed the visual form, “made up of dancers interlacing in a thousand ways” and resembling “garlands, crowns, hoops ornamented with flowers.” This more general use of the term implied harmony, grace, and a sense of lightness, expressed through flowing motion and the even distribution of the body’s weight. In writing on dance during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, this nebulous set of qualities was often conjured up through the visual of a sinuous line. Choreography of the period sometimes incorporated shawls, veils, or garlands that mimicked the drawn arabesque line in three dimensions, creating scrolling patterns that twined around the dancers.

In the modern period, the American dancer and choreographer Loïe Fuller used billowing fabric to create the effect of sinuous line and shifting form in three dimensions. Fuller performed her innovative Serpentine Dance in a voluminous silk costume, projecting a light show of her own design onto its flowing sleeves while she danced to create a shifting and hallucinatory swirl of color. Fuller’s Serpentine Dance thrilled audiences and prompted dozens of artist portrayals, notably inspiring a print by the painter and graphic artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. One of Toulouse-Lautrec’s most experimental forays into arabesque form stemmed from Fuller. At first glance, the “blob” at the center of Toulouse-Lautrec’s print is unrecognizable as a human figure, but a closer inspection reveals Miss Loïe Fuller to be a sophisticated rendering of dance, a time-based art, in just two dimensions. Fuller’s head and feet appear enveloped in her costume’s swirling arabesque contours.

Featuring an essay by Anne Leonard, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, Arabesquetraces the role of this curvilinear decorative motif through a variety of styles and media in European art. An elegant companion to the exhibition, this sixty-four-page softcover publication includes fifty-seven color illustrations highlighting objects from the show and their influences.