July 4–September 21, 2014

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

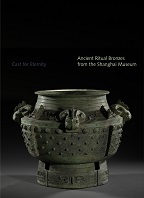

Cast for Eternity: Ancient Ritual Bronzes from the Shanghai Museum is drawn from the core of the Shanghai Museum’s exceptional collection of bronze vessels and bells dating from the Erlitou period to the Han dynasty (eighteenth to the first century BCE). The thirty-two objects in the exhibition show the range of artistic expression and variety of sculptural forms realized during China’s Bronze Age. The exhibition is designed by Selldorf Architects, New York and is the first installation in the West Pavilion of the new Clark Center. Cast for Eternity is on view through September 21, 2014.

This exhibition is organized by the Shanghai Museum and the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts, and is supported by the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation and the Asian Cultural Council.

TRANSCENDENT POWER AND TRANSFORMATIONAL FORMS

Bronze vessels and bells are among the most significant aesthetic and political relics to survive from China’s Shang and Zhou dynasties (16th–3rd century BCE). Dragons with curling bodies, beasts with bared fangs, and other intricately crafted designs embellish these bronzes from the Shanghai Museum—a collection whose scope and quality is without equal. Beneath their lavish surfaces, the vessels preserve a rich cultural history. They were made to contain offerings for ritual ceremonies, channeling the mystical power of ancestors and gods. Bronzes also accompanied nobles to their tombs, preserving their status though the vessels’ inscriptions and material solidity.

The objects on view are arranged by time period and span the broad range of forms and decoration that developed over two millennia. As vessels used in ritual banquets, they have particular shapes and uses. A number of the forms were designed for cooking and serving meat and cereal grains, while others relate to rituals involving heated and cooled wines. Music played on drums and bells accompanied these rituals, heightening the experience of ceremonies that united ancestors with the living, the spirit world with earthly time.

CASTING TECHNIQUES

Lei Wine Vessel with Taotie Animal Masks. Late Shang Dynasty, 12th–11th century BCE

Bronze casting in ancient China was a time- and materials-intensive process that is a marvel of technology. The earliest bronze alloy (copper, tin, and trace metal) cast molds have been dated to c. 1900 BCE.

The first step in the process was the creation of a full-sized model made out of clay—the positive form. Next, a series of negative molds were created by pressing ceramic clay onto the positive form. Usually there was a minimum of three molds to form the body of the smallest vessels.

These piece molds were then kiln fired to allow them to withstand the high temperatures of the molten bronze. Kiln firing makes clay shrink, and so a new positive mold would be made using the set of ceramic piece molds, which would then again be kiln fired.

There is a natural space between ceramic piece molds and ceramic positive molds when assembled and paired for casting. Molten bronze is poured into this space. Bronze often seeped out from the seams where the multiple piece molds came together.

After cooling, the piece molds were removed and the positive mold was dug out from the interior of the bronze cast. Leaving the flanges—the bronze edges that had seeped out during the pouring process—became a fashion and part of the design of many bronzes. In some pieces they are stylized to appear part of the design, while in others, they are left in the original state.

DESIGN MOTIFS

Pou Wine Vessel with Four Ram Heads (detail). Late Shang Dynasty, 13th–11th century BCE

Whether appearing in bas-relief design across the body of a vessel or comprising the entire object shape itself, mythical beasts and animals were the prominent design motif of the Bronze Age. Imbued with supernatural powers, owls (the night hunters, perhaps lords of the underworld), oxen and rams (the strong champions of the earth), raptor birds (lords of the sky), and venomous snakes were the most popular, and were often combined to create even more powerful composite beasts. The taotie, a mask formed by an ox head and spiraling horns, is a specific motif found repeatedly in this group of vessels. It is believed to ward off evil.

CEREMONIAL USE OF BRONZES

Zhi Wine Vessel with Taotie Animal Masks. Late Shang Dynasty, 13th–12th century BCE

In China, bronze vessels were used in banquets and rituals as containers for food and wine. During these rituals they were presented as offerings to ancestors and animalistic gods. They have also often been found in royal burial sites. Their association with ancestor worship made them symbols of political power. The variety and number of ritual bronzes arrayed in the tombs appear to indicate the status and authority of the deceased within the aristocracy. Thus, ritual bronzes not only helped the deceased gain privileged access to the spirit world, but also allowed them to maintain their hierarchical status in the afterlife.

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

A fully illustrated catalogue accompanies the exhibition, with essays by Zhou Ya, senior curator of ancient bronzes at the Shanghai Museum, and Liu Yang, curator of Chinese art and head of the Department of Asian Art at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. The catalogue is published by the Clark and distributed by Yale University Press.

Call the Museum Store at 413 458 0520 to order.