JULY 12–DECEMBER 13, 2020

Image Gallery

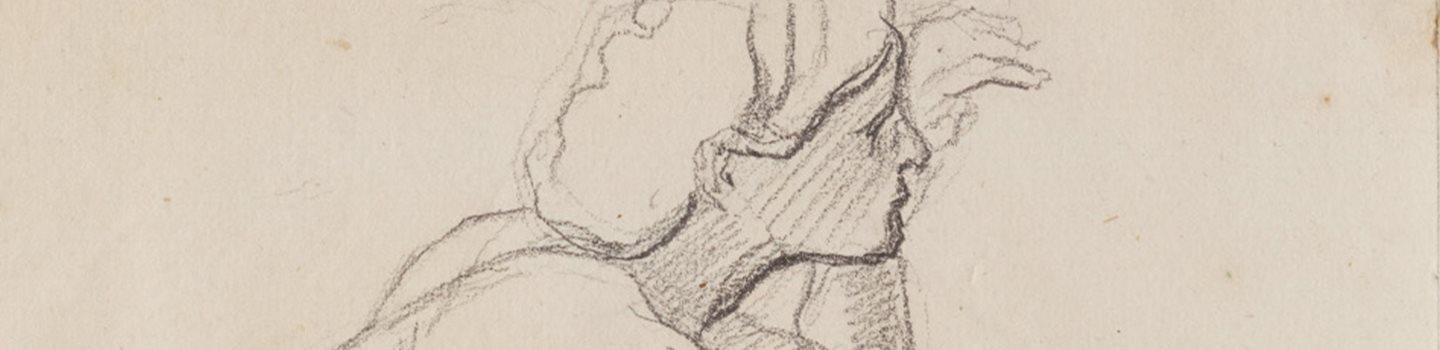

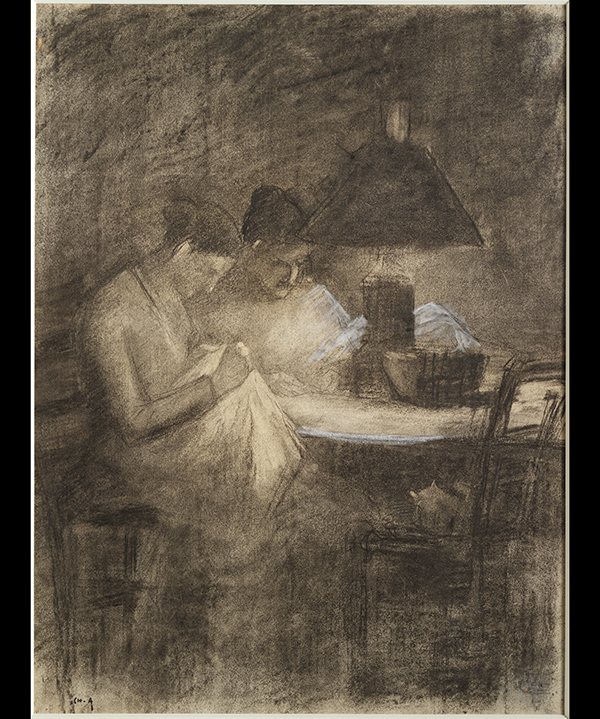

JEAN-AUGUSTE-DOMINIQUE INGRES

FRENCH, 1780–1867

A COUPLE EMBRACING

c. 1813–14

Graphite on paper

6 5/16 x 4 13/16 in.

Collection of Herbert and Carol Diamond

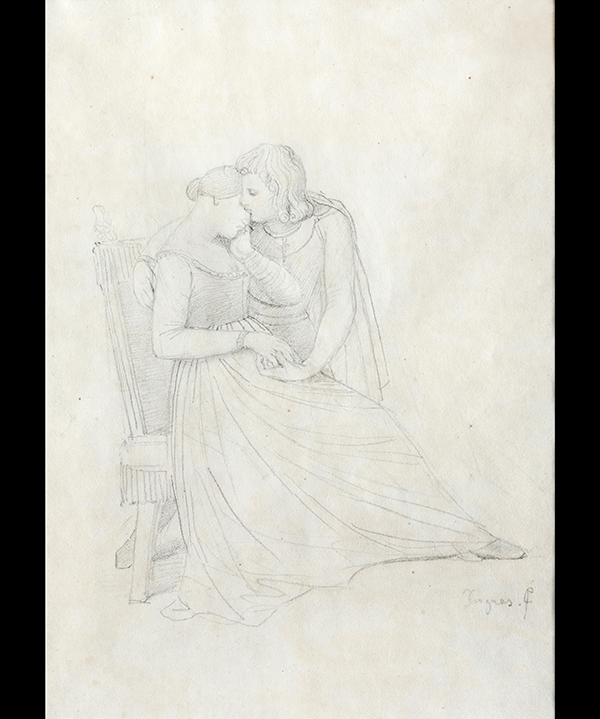

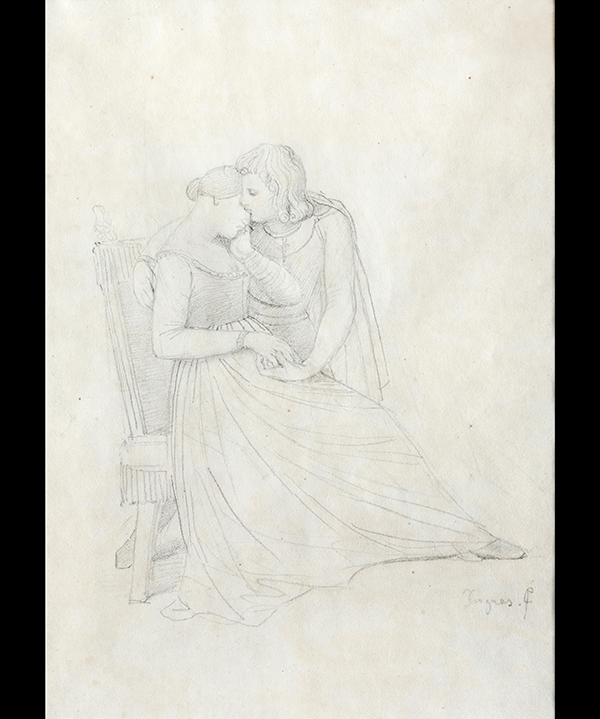

JEAN-AUGUSTE-DOMINIQUE INGRES

FRENCH, 1780–1867

BATHING WOMAN

1828–67

Graphite on pinkish-beige prepared paper

9 5/8 × 7 5/16 in.

Clark Art Institute

Gift of Herbert and Carol Diamond

2017.10.5

In this drawing, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres emphasizes the essential contours and mass of a bather wringing her luxuriant hair. The tight framing of the sheet calls attention to the pronounced, harmonious curves of her pose—and her stylized proportions, drawn in disregard for anatomical accuracy. The figure’s smooth profile resembles the idealized beauty of antique statuary, rather than bearing individualized features that indicate the artist drew from life. Ingres returned to the theme of bathers throughout his career, from his early Valpinçon Bather (1806)—an exercise completed as part of his Prix de Rome scholarship—to his late Orientalist fantasy of concubines in a harem, The Turkish Bath (1862).

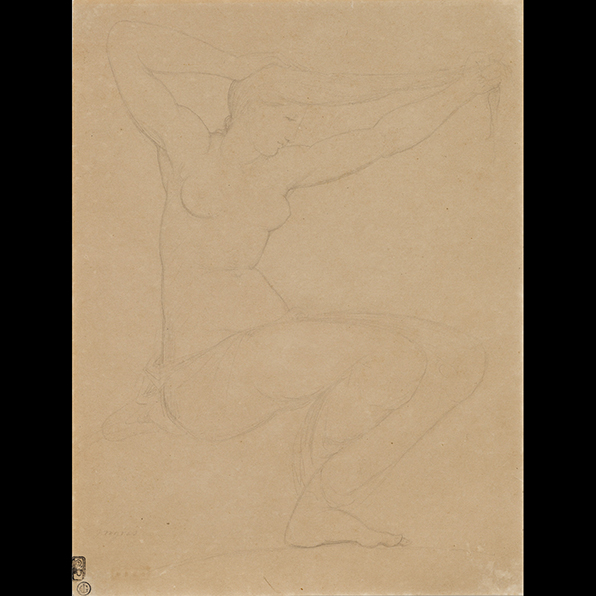

EDGAR DEGAS

FRENCH, 1834–1917

FIVE STUDIES OF A HAND

1856

Graphite on paper

5 1/8 x 6 in.

Collection of Herbert and Carol Diamond

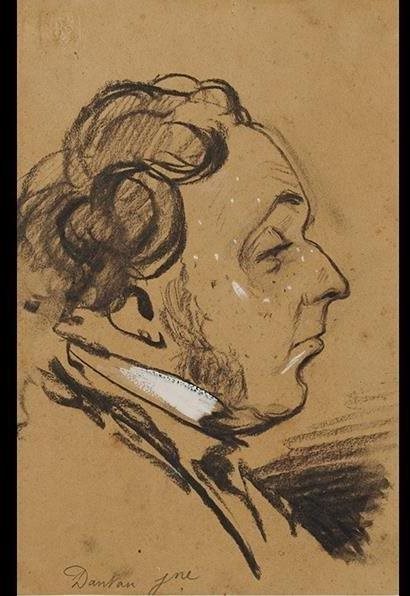

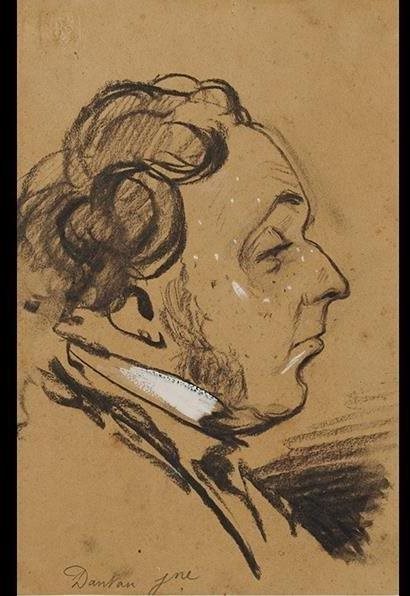

NADAR

FRENCH, 1820–1910

PORTRAIT OF DANTAN JEUNE

c. 1854

Charcoal with stumping, heightened with gouache, on paper

9 3/8 × 6 1/8 in.

Clark Art Institute

Gift of Herbert and Carol Diamond

2018.11.12

Renowned for his photographic portraits of French artistic and literary luminaries, Nadar began his career as a caricaturist. Gaspard-Félix Tournachon adopted his pseudonym—a play on his last name, “tourne à dard” (bitter sting)—in the early 1840s, when he became an illustrator for satirical newspapers. In 1854 he published Panthéon-Nadar, a large-format lithographic group portrait of hundreds of prominent Parisians, figures with oversized heads and spindly bodies that stand in a snaking line. Nadar sketched this simplified, exaggerated profile of sculptor Jean-Pierre Dantan (1800–1969), called Dantan Jeune, in preparation for the monochromatic print. Dantan shared Nadar’s sense of humor: he specialized in caricature busts portraying members of Parisian high society and the July Monarchy government.

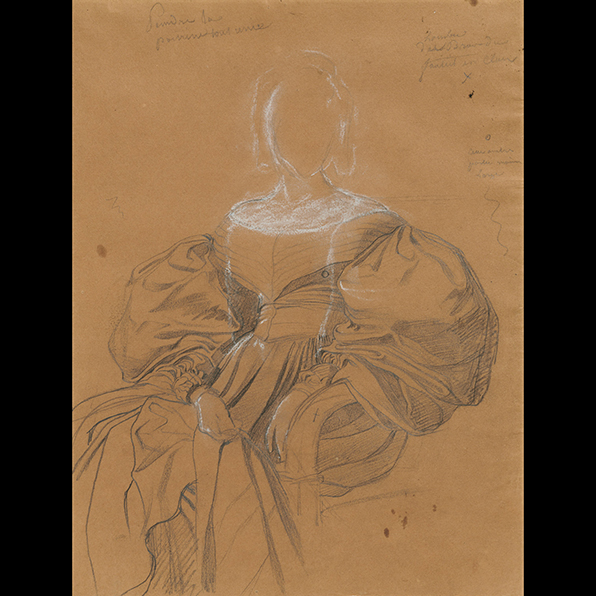

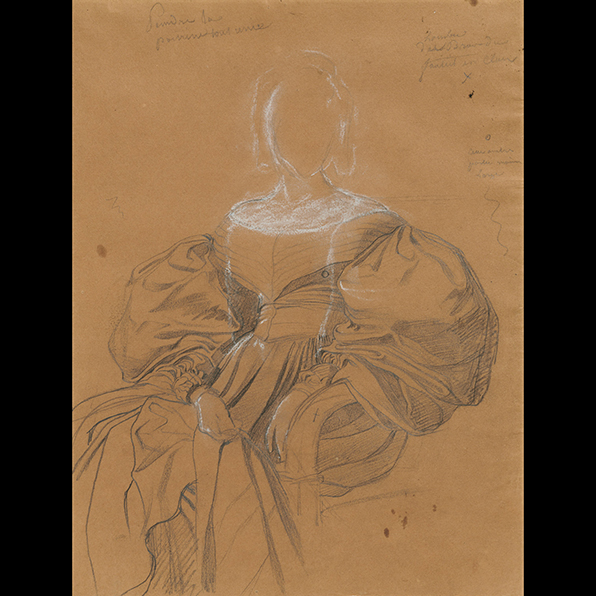

RENÉ-AUGUSTE FLANDRIN

FRENCH, 1804–1843

STUDY FOR WOMAN IN GREEN

c. 1835

Black chalk, heightened with white chalk, on paper

12 × 9 3/8 in.

Clark Art Institute

Gift of Herbert and Carol Diamond

2018.11.9

René-Auguste Flandrin—the eldest brother of artists Hippolyte and Paul, whose work is on view nearby— specialized in portraiture. In this drawing, René leaves the face, the crux of likeness in portraiture, featureless. He sketches out the sitter’s head and shoulders while giving contour and shadow to the billows and folds of her dress. White chalk lines trailing over her chest to her hands indicate where René would depict a long jeweled necklace in the painting Woman in Green (1835). Annotations in the upper part of the sheet explicitly refer to brushwork, while the reference to a “loge” hints at props still to come: in the painting, a pair of opera glasses rests in the sitter’s left hand.

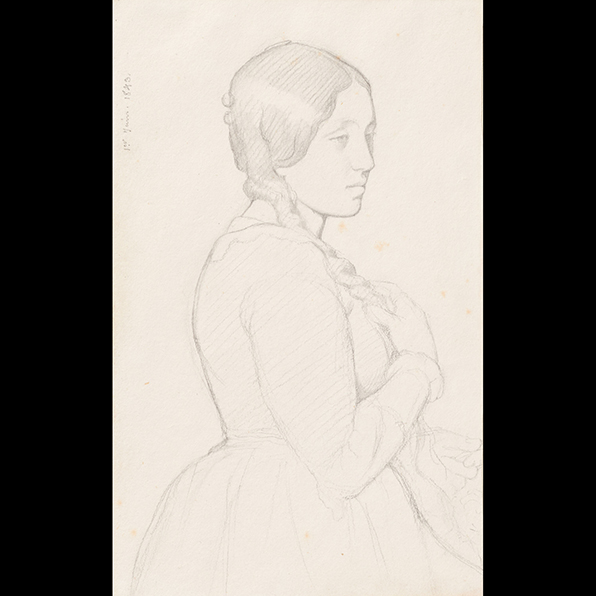

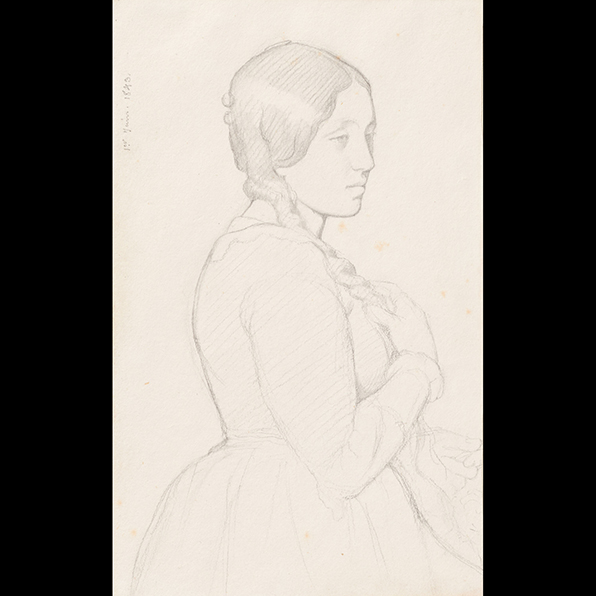

PAUL FLANDRIN

FRENCH, 1811–1902

PORTRAIT OF A WOMAN

1843

Graphite on paper

7 1/4 × 4 1/2 in.

Clark Art Institute

Gift of Herbert and Carol Diamond

2018.11.7

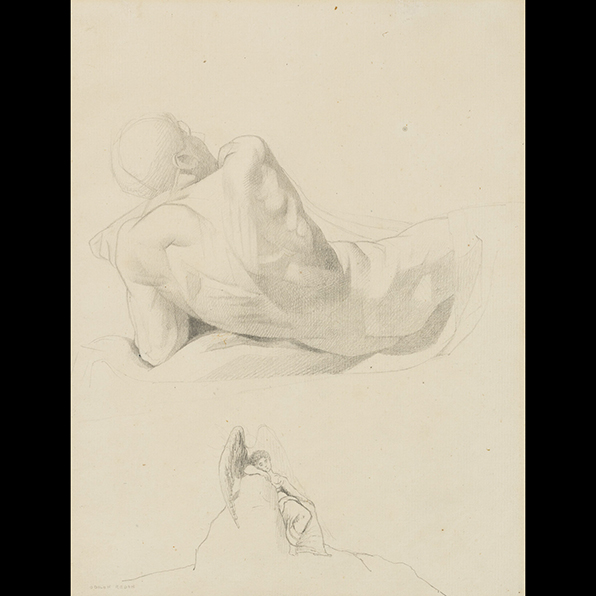

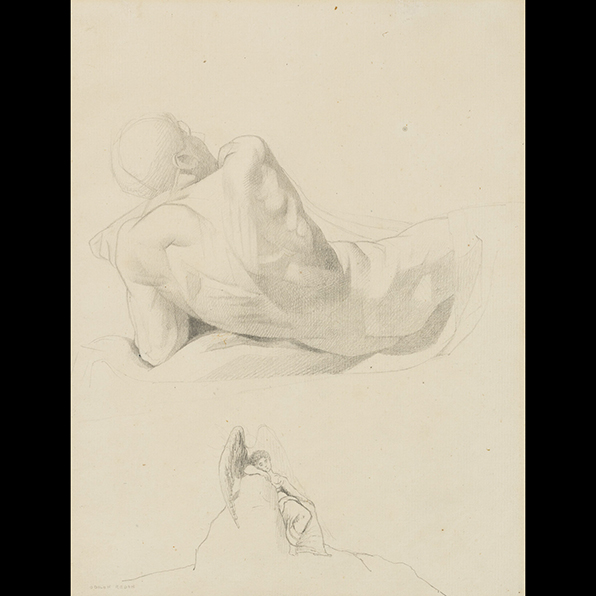

ODILON REDON

FRENCH, 1840–1916

STUDY OF A MAN’S BACK AND A MELANCHOLY ANGEL

1865

Graphite on paper

11 1/2 × 8 3/4 in.

Clark Art Institute

Gift of David Jenness, in honor of

Arthur F. Jenness (Professor, Williams College, 1946–1963)

2016.7

This anatomical study of a reclining man’s back displays Redon’s efforts in hatching, a technique of modeling form with thin, closely laid parallel lines. In 1865 Redon’s teacher, academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, dismissed this type of drawing as calling too heavily on his imagination. Redon likely added the angel—sketched simply, with limited shading—to the bottom of his sheet after he left Paris. Invoking the iconic winged figure in Albrecht Dürer’s engraving Melencolia I (1514), the images of earthbound angels looking upward soon graced many of the artist’s student works. Back home in his native Bordeaux, Redon found a kindred spirit in idiosyncratic printmaker Rodolphe Bresdin (1822–1885), who encouraged his nascent unconventional visual language.

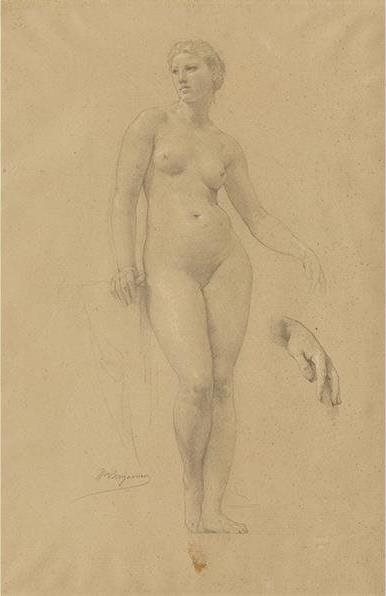

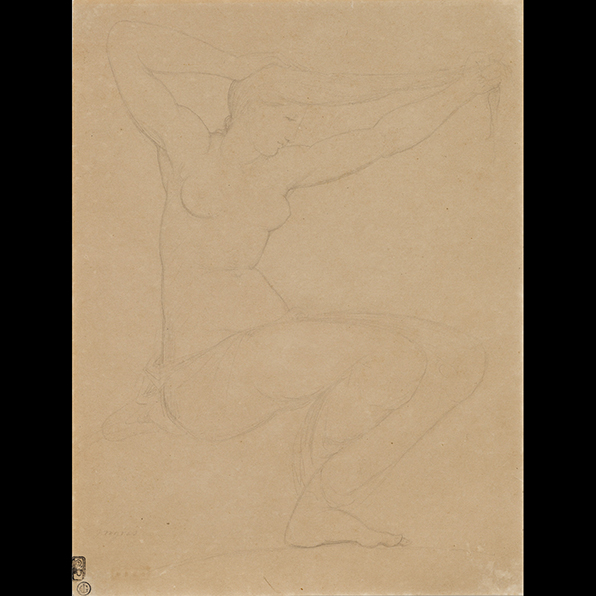

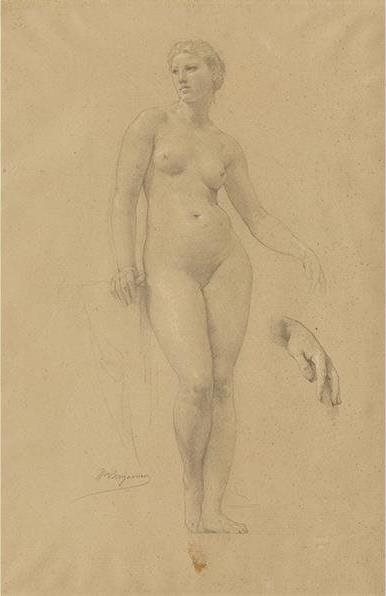

WILLIAM-ADOLPHE BOUGUEREAU

FRENCH, 1825–1905

STUDY OF VENUS FOR APOLLO AND THE MUSES IN OLYMPUS

c. 1867

Graphite with touches of white chalk on paper

18 7/16 x 12 in.

Clark Art Institute

Acquired by Sterling and Francine Clark

1955.1578

This sculpturesque study of a nude woman exemplifies William-Adolphe Bouguereau’s strict adherence to the tenets of academic proportion and modeling. Bouguereau legitimizes the figure’s nakedness—heightened by the abandoned garment draped conspicuously behind her—by depicting her as Venus, the Roman goddess of love. In the fully developed multi-figure painting Apollo and the Muses in Olympus (1869), Venus stands among the spellbound audience of deities listening to Apollo strumming his lyre. Her left arm extends, as indicated lightly here, to embrace her son Eros. Bouguereau worked up the separate, enlarged detail of Venus’s left hand to practice convincingly rendering her fingers, which gently press into Eros’s shoulder.