.jpg)

MARCH 5–MAY 29, 2017

Image Gallery

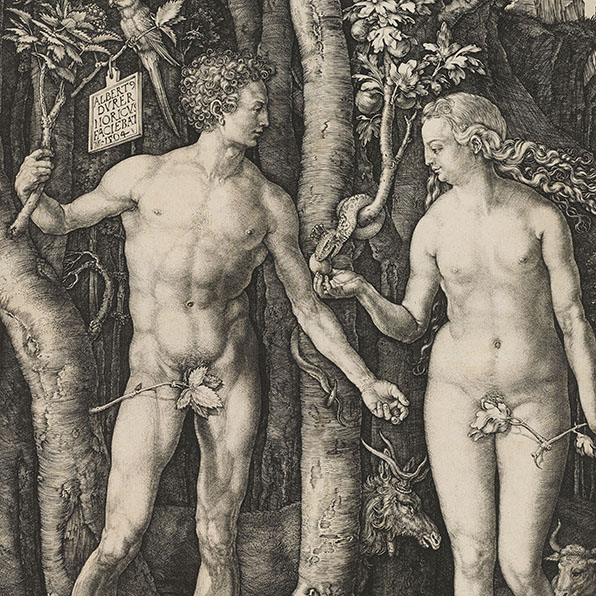

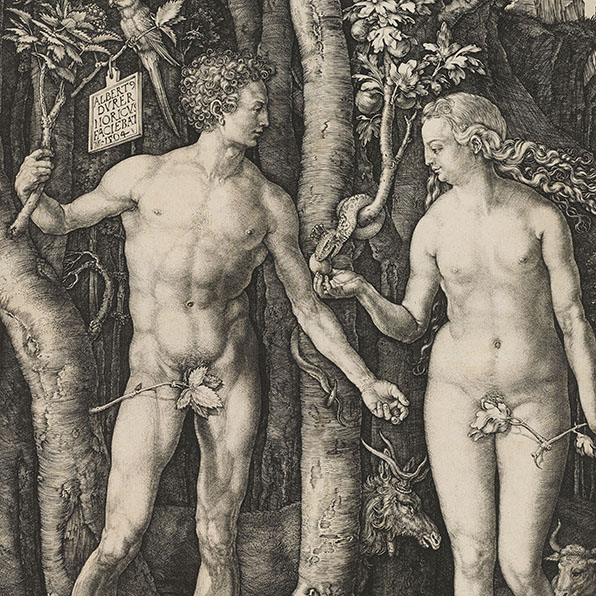

ALBRECHT DÜRER

GERMAN, 1471–1528

ADAM AND EVE

1504

Engraving on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 1968.56

In his depiction of Adam and Eve, Albrecht Dürer applied a system of proportions to achieve what he considered an idealized human form. Based on his study of the ancient Roman theorist Vitruvius, as well as antique statuary he encountered in Italy, Dürer developed a set of ideal measurements that would later appear in the Four Books on Human Proportion (1528). Here, the nude figures of Adam and Eve mirror each other with graceful poses and gestures inspired by the classical example.

SEBASTIAN VRANCX

FLEMISH, 1573–1647

ANNA AND DIDO DISCUSS AENEAS

c. 1615

Black chalk, pen and brown ink, and wash on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute

Gift of Alice Steiner, 1997.7

Sebastian Vrancx’s drawing, which formed part of a series depicting scenes from Virgil’s epic poem The Aeneid, seamlessly integrates the figures into a detailed architectural setting. Rather than focusing on the facial features or expressions of the two women, who are simply delineated, Vrancx concentrated on the narrative moment and surrounding palace architecture. This setting may have been inspired by the perspective studies of the Dutch architect Hans Vredeman de Vries, whose work was widely known in the Netherlands. Like many of his contemporaries, Vrancx also traveled to Italy early in his career, but continued to integrate northern traditions into his work in an example of local artistic exchange.

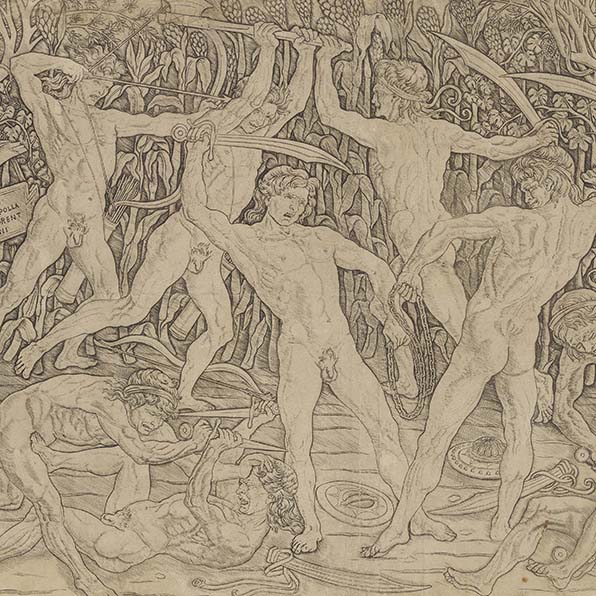

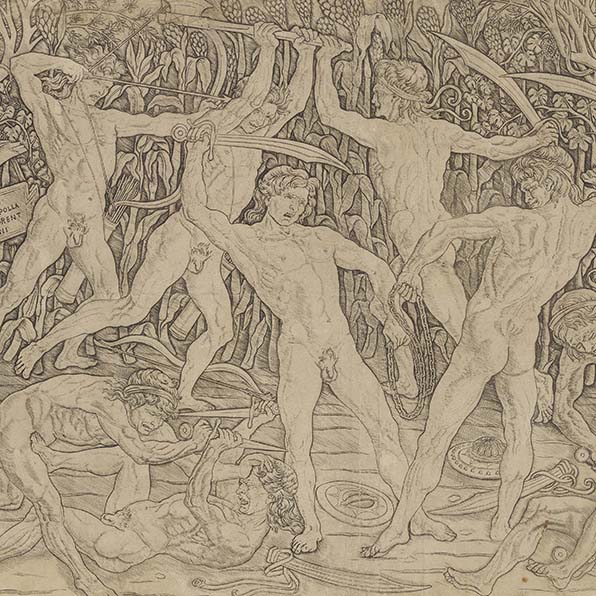

ANTONIO DEL POLLAIUOLO

ITALIAN, 1431/1432–1498

BATTLE OF THE NAKED MEN

c. 1470 (printed c. 1625)

Engraving on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 1955.1425

A sculptor, goldsmith, painter, and engraver, Antonio del Pollaiuolo depicted the human body with strong contours and exaggerated musculature in this chaotic battle scene. The figures, seen from multiple perspectives, charge and thrust their weapons with grimacing faces. Pollaiuolo used parallel shading (hatchings applied in close clusters of parallel lines) to emphasize the strained muscles of the men and their active poses. The artist’s knowledge of classical statuary is evident in the men’s idealized forms and the strong horizontal orientation of the narrative, which reflects compositions found on ancient sarcophagi. Due to its unusual size and subject, the print may have served as a pattern sheet offering exemplary models for other artists, but it also affirmed Pollaiuolo’s ability to represent the human form.

GIOVANNI ANTONIO BOLTRAFFIO

ITALIAN, C. 1467–1516

HEAD OF A WOMAN

c. 1495–97

Metalpoint heightened with white on gray prepared paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 1955.1470

In the soft handling of the woman’s head and gentle curls that frame her face, Giovanni Boltraffio demonstrated his skill in portraying facial features with extraordinary delicacy. The deep shadow on the right side of the woman’s face—emphasizing the hint of a smile—and the sfumato (gradual shading) effect that shapes her cheek reflect the character and technique of the work of Boltraffio’s teacher, Leonardo da Vinci. This sensitive study may have served as a preliminary drawing for a painting of the Madonna and Child, but its remarkable directness and assured handling suggest that it could also have been an independent work.

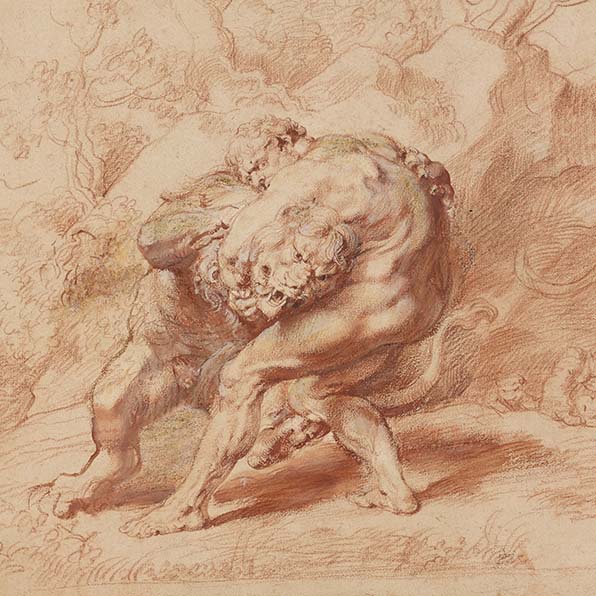

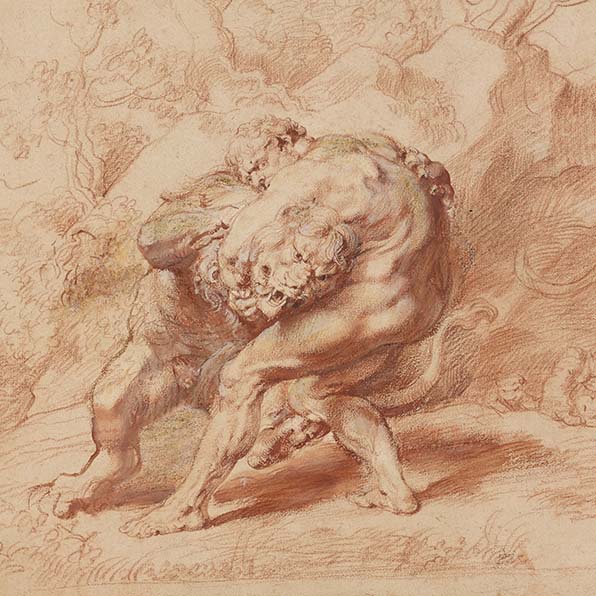

PETER PAUL RUBENS

FLEMISH, 1577–1640

HERCULES STRANGLING THE NEMEAN LION

c. 1620

Colored chalks, brush and red ink, and gouache on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 1955.992

Peter Paul Rubens’s interlocked muscular forms depict a scene from the Twelve Labors of Hercules, a series of tasks the Greek hero completed that resulted in his immortality. The drawing, which likely originated during Rubens’s stay in Italy from 1600 to 1608, demonstrates his adaptation of poses from classical statuary. Hercules’s highly articulated muscles and twisted posture reflect the Farnese Hercules, a renowned antique sculpture in Rome. Here, Rubens utilized red chalk and white gouache highlights to evoke the soft, living flesh of the man, rather than the cool, hard marble of the sculptures that inspired him.

REMBRANDT VAN RIJN

DUTCH, 1606–1669

NATHAN ADMONISHING DAVID

c. 1652–53

Pen and brown ink on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 2003.9.29

Quick, gestural lines and single, controlled strokes of the pen describe the features, drapery, and setting in Rembrandt’s sketch of a biblical subject. This small-scale, narrative drawing is an example of the Dutch artist’s economical technique when rendering the human form and evoking physiological tension. Rembrandt often drew the same subject several times to explore its complexities. This work is the earliest of three drawings representing the prophet Nathan rebuking King David from the Old Testament (2 Samuel 12:1–14). Compared to fully realized works, Rembrandt’s sketches capture an idea in progress, akin to our own modern conception of sketching.

MAARTEN DE VOS

FLEMISH, 1532–1603

RAPE OF THE SABINE WOMEN

c. 1585

Pen and brown ink with wash on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 2003.9.22

In Maarten de Vos’s large-scale historical scene, figures turn and struggle in contorted positions to create a dense and multilayered composition. Strong diagonals punctuate the landscape and lead the viewer’s eye to the horizon, where several prominent Roman sites are visible, including Saint Peter’s basilica and the Column of Trajan. After a visit to Italy in the 1550s, which likely included stays in Rome and Venice, De Vos returned to his native Antwerp. There, he associated with the so-called Romanists, a religious brotherhood that included a number of artists whose work was similarly informed by Italian art.

GIOVANNI MARIA TAMBURINI

ITALIAN, DIED AFTER 1660

STREET WITH TRADESMEN

Late 16th–early 17th century

Pen and brown ink over red chalk on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 1978.14

Giovanni Maria Tamburini’s drawing illustrates an array of street trades situated in a frieze-like format across an Italian palazzo. Figures harmonize with the surrounding environment of shops and architectural details, carrying jugs of water, barrels of wine, or bunches of onions. Tamburini specified each activity and some of the architecture with inscriptions, including charming details like the young boys who wait eagerly for freshly roasted chestnuts in the left foreground. The Bolognese artist Francesco Curti turned each of Tamburini’s drawings of the trades into etchings for a series called Virtù et Arti Essercitate in Bologna. Both artists would likely have been influenced by earlier depictions of the trades, particularly those by their Bolognese contemporary, Annibale Carracci.

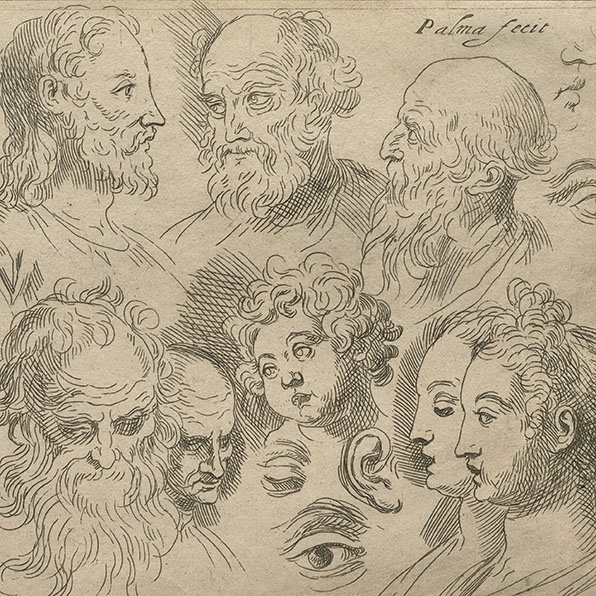

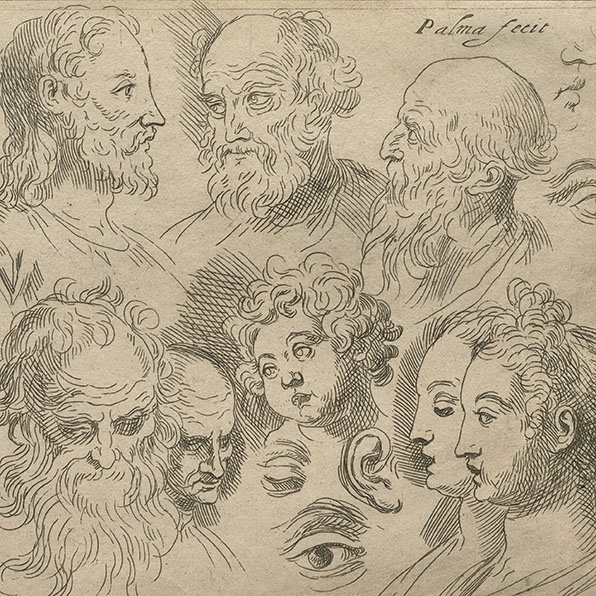

JACOPO PALMA IL GIOVANE

ITALIAN, C. 1548–1648

TEN HEAD STUDIES

1636

Etching on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 1987.49

The loosely sketched, densely arranged head studies in this etching illustrate the drawing method that Jacopo Palma helped popularize in Venice in the early seventeenth century. The figures, seen from various perspectives and representative of different ages and types, are interspersed with depictions of eyes, noses, and ears. Although the origins of this print are unknown, it relates to the images found in drawing books, which formalized a method of progressive learning around the human form. This approach quickly spread to Northern Europe, where drawing books were used by art students and amateurs alike.

GIORGIO VASARI

ITALIAN, 1511–1574

THE INCREDULITY OF SAINT THOMAS

c. 1556–57

Pen and brown ink and wash with black chalk on paper (detail)

Clark Art Institute, 2003.9.4

Giorgio Vasari, widely known for his Lives of the Artists, a series of biographies first published in 1550, was also active as a painter of canvases and frescoes. For large commissions, which required the assistance of his workshop for completion, Vasari often first made preliminary drawings. This sketch, surrounded by a framing device, depicts the doubting Saint Thomas from the Gospel of John (John 20:24–29). Overlaid grid sections indicate that the artist intended to have the densely packed figural group copied at a larger scale onto the final composition. No extant painting can be associated with this study, but it is an excellent example of the precise drawing technique that was prominent in sixteenth-century Italy.

BOETIUS ADAMS BOLSWERT AFTER PETER PAUL RUBENS

BOETIUS ADAMS BOLSWERT (FLEMISH, 1580–1633)

PETER PAUL RUBENS (FLEMISH, 1570–1640)

THE RAISING OF LAZARUS

c. 1631–32

Engraving (detail)

Clark Art Institute

Gift of David P. Tunick, 2009.14.2

Reproductive prints—prints that translated singular works of art (predominantly painting) into multiples that could be distributed far and wide—were a fundamental mechanism of the artistic exchange of this period. Peter Paul Rubens took an active role in the publication of reproductive engravings after his work throughout the course of his career, maintaining a close relationship with such printmakers as Boetius Adams Bolswert. Bolswert worked on five engravings after Rubens’s religious scenes, including The Raising of Lazarus, devoting particular attention to the painter’s technique in modeling the body. Rubens’s close supervision of this work ensured its high quality, making it an important tool for publicizing the artist’s inventions.