JUNE 8–SEPTEMBER 22, 2019

CLASSICAL IMPRESSIONISM

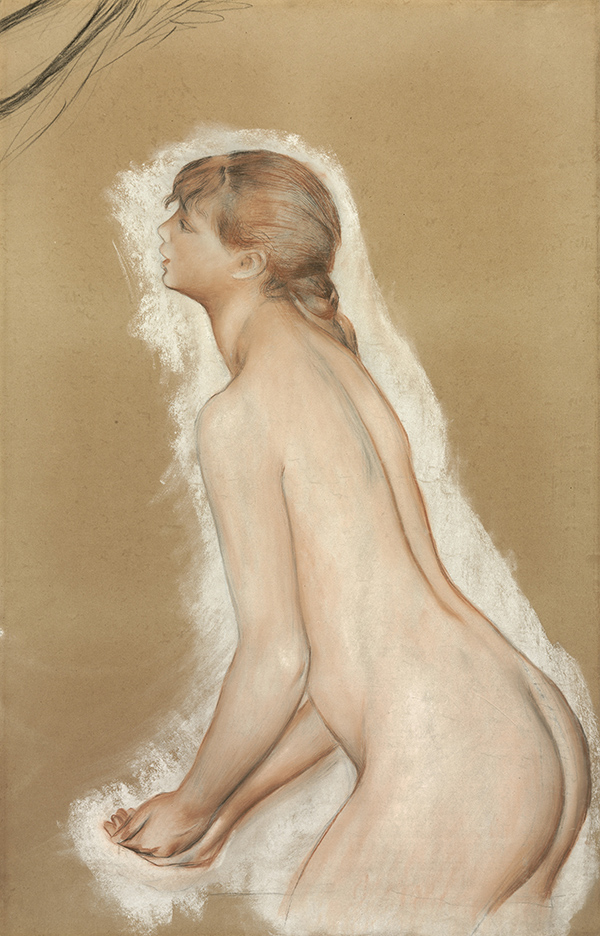

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919), Splashing Figure (Study for The Great Bathers), c. 1884-87. Red, white, and black chalk, with stumping and black conté crayon on tan wove (tracing) paper, laid down on canvas, 38 15/16 × 25 in. Art Institute of Chicago. Bequest of Kate L. Brewster, 1949.514

At the height of his engagement with Impressionism in the 1870s, Renoir dismissed the period of study that students at the École des Beaux-Arts were encouraged to take in Rome and criticized returning painters “with the ambition of emulating Raphael” as “ridiculous.” Visiting Italy for the first time in 1881, however, the forty-year-old Renoir reversed his position and embraced the lessons of Raphael. Traveling with his future wife, Aline Charigot, Renoir visited many sites, including Venice, Padua, Florence, Naples, Capri, and Rome. Raphael’s frescoes at the Villa Farnesina in Rome made a particularly strong impression, and he wrote enthusiastically to his dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, in Paris: “I have seen the Raphaels. I should have seen them earlier. They are full of knowledge. His frescoes are admirable in their simplicity and grandeur.” Renoir’s style and repertoire transformed as he emerged from a self-proclaimed “crisis of Impressionism” following this trip.

Renoir’s stylistic “crisis”––his search for rigorous lines and structure while retaining the vibrancy of his Impressionist palette––resulted in a period of Classical Impressionism. This formal shift set him at odds with his dealer and many of his peers, threatened his economic well-being, and ended only after he concluded painting The Great Bathers in 1887. Renoir may have considered the monumental canvas to be his “masterpiece,” yet it was a polarizing work among the avant-garde because of its classicizing aesthetic. It remained unsold for two years after it was first displayed at the Sixth International Exposition at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris in May–June 1887. While Claude Monet lauded his friend’s “superb picture,” Camille Pissarro found the finished painting “incoherent.”

Renoir created at least twenty preparatory drawings and figure studies in various formats and media, many of which were ambitious, heavily worked, and large in scale. Berthe Morisot admired these sheets during a visit to Renoir’s studio in January 1886. She wrote in her diary: “It would be interesting to show all these preparatory studies for a painting to the public, which generally imagines that the Impressionists work in a very casual way. I do not think it is possible to go further in the rendering of form. . . . He told me that for him the nude was one of the indispensable forms of art.”

Offering the first-ever comprehensive investigation of Renoir’s nudes, Renoir: The Body, The Senses was published by the Clark Art Institute and edited by the exhibition’s curators, Esther Bell, Robert and Martha Berman Lipp Chief Curator of the Clark Art Institute, and George T. M. Shackelford, deputy director of the Kimbell Art Museum. This beautifully illustrated catalogue includes essays by Colin B. Bailey, Morgan Library & Museum; Martha Lucy, Barnes Foundation; Nicole R. Myers, Dallas Museum of Art; and Sylvie Patry, Musée d’Orsay; with an interview between contemporary figurative painter Lisa Yuskavage and Alison de Lima Greene, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.