June 14–September 13, 2015

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890)

Butterflies and Poppies, 1890

Oil on canvas, 35 x 25.5 cm

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

For Vincent van Gogh, nature was the defining subject of his art. Over the course of his short but intense working life, Van Gogh studied and depicted nature in all its forms—from the minutiae of insects and birds’ nests to the most sweeping of panoramic landscapes—creating a body of work that revolutionized the representation of the natural world at the end of the nineteenth century.

HOLLAND

1881–1885

“Nature is certainly pure here.”

Van Gogh was born in the southern Netherlands, where he spent his youth and was encouraged to read and to enjoy his rural surroundings. One of his sisters remembered that “he knew all the places where rare flowers grew” and “all the names of the beetles” that he preserved in little boxes. Over time he tried unsuccessfully to become a print dealer, a schoolteacher, and a pastor (like his father) before committing himself to studying art in his mid-twenties.

Initially depicting the Dutch landscape and rural workers in the somber tones used by painters like Théodore Rousseau and Jean-François Millet, Van Gogh also worked hard at drawing and eventually produced skillful studies of gardens, birds’ nests, and trees. Vincent wrote to his brother Theo in 1883 about his attempts “to work faithfully and forcefully from nature,” while painting outdoors and also learning about new developments in art elsewhere. The following year he discovered the radical color theories of Charles Blanc and experimented with a brighter palette in works such as Poplars near Nuenen before moving to Paris in 1886.

PARIS

1886–1888

“With a sincere personal feeling of colour in nature I would say an artist can get on here.”

Van Gogh left rural Holland in late 1885 in search of lessons in drawing and painting and firsthand experience of modern art. After a brief stay in Antwerp, he arrived in Paris in February 1886. Vincent studied at the Louvre and attended classes elsewhere with other young artists, soon abandoning the somber hues of his Dutch years in favor of a modified Impressionist manner. Claiming that “a sincere personal feeling of color in nature” allowed artists to make progress in Paris, he produced large numbers of flower paintings that he attempted to sell, though with little success.

Lodging with his brother Theo (a rising art dealer in Paris) in an apartment in Montmartre high above the city, Van Gogh made experimental compositions of gardens and restaurants. Increasingly confident, he was befriended by such artists as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Émile Bernard, whose work encouraged Van Gogh to tackle views of Paris itself. Paintings of city parks and bridges across the river Seine followed, some with recently built apartments in the distance. More lasting was the influence of landscapes by Claude Monet, which Van Gogh saw for the first time in an 1886 exhibition.

AUVERS

1890

“Before such nature I feel powerless.”

Aware of his declining health and wishing to be nearer to his brother and family, Van Gogh traveled north in May 1890 and stayed in Auvers-sur-Oise, a small rural town northwest of Paris. It was far enough from the city “to be in the real countryside,” he reported on arrival and was “covered with flowers” and “almost lush.” Working outdoors nearly every day, he immediately began drawing and painting his surroundings, including trees, flowers, and sweeping landscapes, as well as fellow residents.

In House at Auvers Van Gogh seems to celebrate this lush environment, while the panoramic Wheat Fields with Reaper revisits a theme that persisted throughout his career. Bolder than ever in his colors and brushwork, his radiant compositions—such as Green Wheat Fields, Auvers—promised new departures in depicting nature. Letters reveal that he knew his health was failing, yet he labored on a series of spectacular views—among them the movingly spare Rain-Auvers, made within days of his death—that show little but sky, earth, and the elements. In late July, Van Gogh died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. In an unfinished letter he admitted that “before such nature I feel powerless.”

PROVENCE

1888–1890

Van Gogh was familiar with Provence primarily from the novels of such writers as Émile Zola and Alphonse Daudet. Certain painters he admired, like Paul Cézanne and Adolphe Monticelli, had also offered glimpses of the largely unspoiled countryside that borders the Mediterranean and enjoys a warm climate.

Arriving in the town of Arles in late February 1888, Van Gogh immediately began painting “a Provence orchard of tremendous gaiety” and announced that he was already working in “a calm frame of mind.” With life in the capital behind him, he depicted almond, peach, and apricot blossoms as well as irises and other flowers growing wild beside fields. “Nature here is extraordinarily beautiful,” he insisted, tackling unfamiliar trees and shrubs and even birds, moths, and insects.

In December he suffered his first mental breakdown and voluntarily entered the local hospital. In May 1889 he transferred to a more specialized hospital in Saint-Rémy, some fifteen miles away.

ARLES

February 1888–May 1889

“I find nature here is almighty beautiful.”

Noting that people had “to be strong to endure life in Paris,” Van Gogh left the city by train in February 1888 and headed south to Arles. Welcoming the “hard blue” sky and “great bright sun,” he immediately began painting his new surroundings in vivid colors as the weather warmed. “My eyes are adjusting to nature here,” he wrote excitedly to his brother Theo as he depicted the local terrain, including less familiar trees such as cypresses, planes, and cedars as well as abundant irises and sunflowers.

Arles also prompted letters on widely varying subjects, from novels he read to glimpses of an interest in science. Vincent discussed astronomy and, unlike Monet (whom he said overlooked “laws of nature”), attempted to identify the species of insects he drew and painted. Even as Van Gogh grew more confident as a painter and draftsman, and despite an extraordinary output, he was increasingly troubled by depression and erratic behavior.

SAINT-RÉMY

May 1889–May 1890

“In the face of nature it’s the feeling for work that keeps me going.”

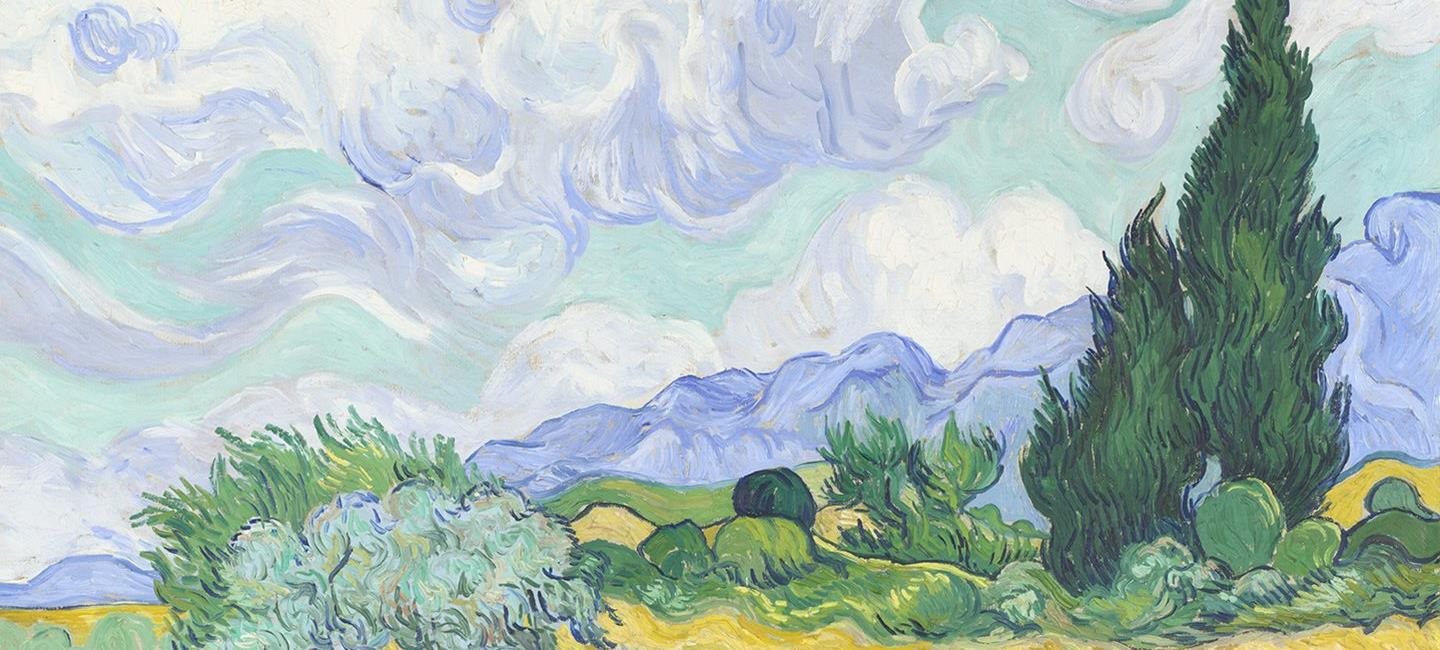

In little more than a year at the hospital in Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh painted around 150 pictures that include many of the most remarkable and original works of his career. Voluntarily entering the institution, he was gradually allowed to paint and draw indoors and later in nearby gardens and fields. The isolated hospital building, formerly a monastery, faced farmland and rocky hillsides dotted with pines, cypresses, and olive trees.

Some of his priorities remained unchanged: “I still have work to do,” he wrote to Theo from Saint-Rémy, noting that “nature is beautiful.” His letters and drawings also refer to small creatures that he saw, such as moths and sparrows, and to the “dandelions . . . daisies and violets” that he sometimes painted. As in Holland, the changing seasons again preoccupied him, most strikingly in a series of canvases that show the view through his window.

In most of these pictures a rhythmic vitality unites hillsides, rock formations, olive trees, and even plants. Explaining his approach to an admirer, Van Gogh wrote of “the emotions that take hold of me in the face of nature.”

A fully illustrated catalogue that chronicles the artist’s ongoing relationship with nature throughout his entire career accompanies the exhibition. Vivid color photography and explanatory texts based on new research clarify this central theme of Van Gogh’s oeuvre. The catalogue is published by the Clark and distributed by Yale University Press. Call the Museum Store at 413 458 0520 to order.

Van Gogh and Nature is made possible by the generous contributions of Denise Littlefield Sobel and Diane and Andreas Halvorsen. Major support is provided by Acquavella Galleries and the National Endowment for the Arts, with additional support from Howard Bellin; the Consulate General of the Kingdom of The Netherlands; the Robert Lehman Foundation; and the Netherland-America Foundation. This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.