The Tapestry Revival

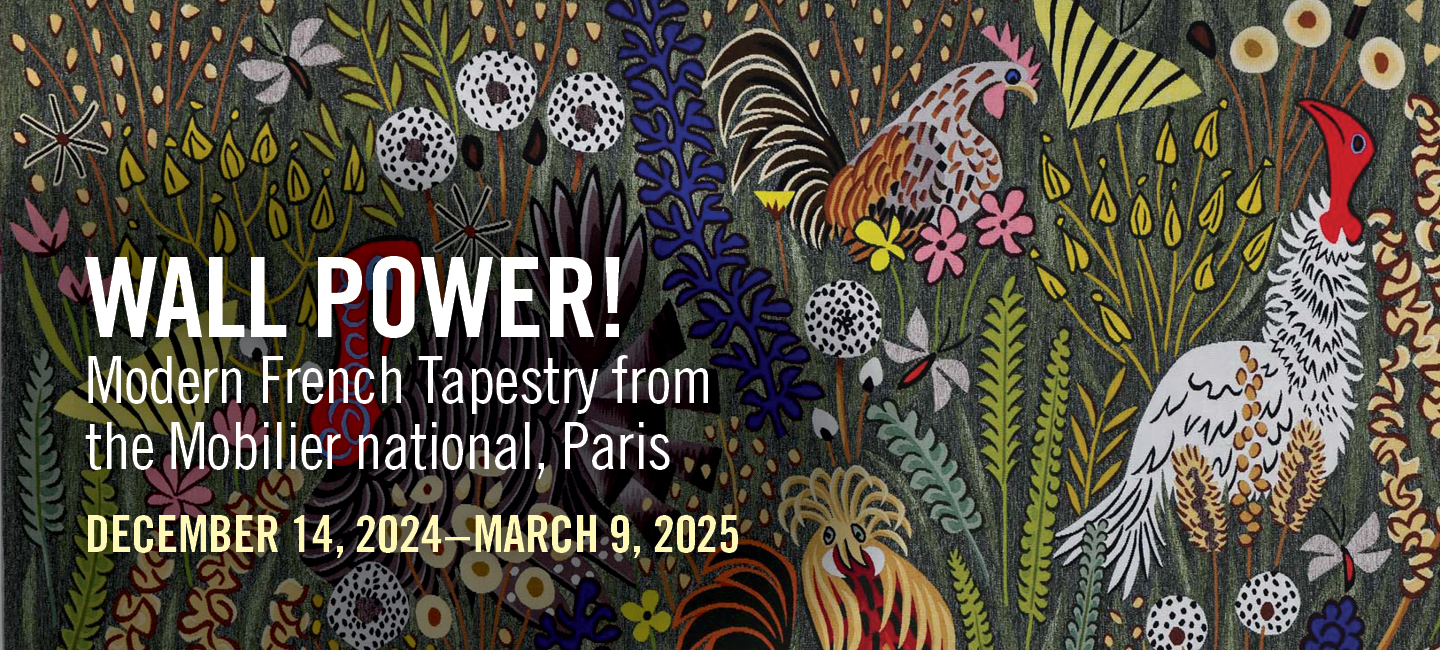

Marc Saint-Saëns, Orphée (Orpheus), woven March 18, 1948–July 3, 1950, wool. Mobilier national, Paris, France, GOB-917, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Philippe Sébert

Marc Saint-Saëns, Orphée (Orpheus), woven March 18, 1948–July 3, 1950, wool. Mobilier national, Paris, France, GOB-917, © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris. Photo: Philippe SébertDespite tapestry’s ancient and treasured heritage in France, by the early twentieth century the industry was in decline. Because of the extremely labor–intensive nature of tapestry making, the finished works are inherently expensive. Tastes had changed but tapestry makers were still creating old–fashioned products that replicated the illusionism of oil painting. In the 1930s various artists, administrators, and entrepreneurs began experiments to align tapestry making in France with currents of contemporary art. One such experiment was particularly successful. In 1939 the French government tasked three artists—Pierre Dubreuil, Marcel Gromaire, and Jean Lurçat—to work alongside weavers in the private ateliers at Aubusson, a commune in the center of France. Led by the vision of Lurçat, these artists collaborated with weavers to create a contemporary style of tapestry that adopted techniques and design approaches from medieval times, but with a distinctly modernist look. With a broad weave, a limited palette of colors, and original designs, the results of what became acclaimed as a “tapestry revival” emerged at the end of the Second World War to become a phenomenon in Europe and North America.