JULY 4–SEPTEMBER 27, 2015

TIMELINE

Whistler’s studio and home, 2 Lindsey Row, London

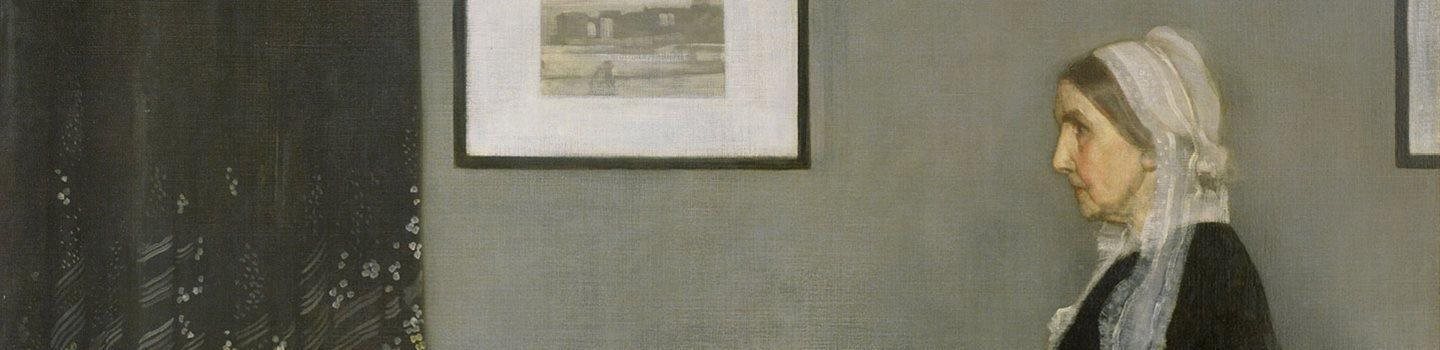

WHISTLER’S MOTHER IN THE AMERICAN IMAGINATION

In the twentieth century, Whistler’s portrait of his mother became an important symbol for Americans. During the Great Depression, a nationwide tour of the painting incited a wave of patriotic pride and nostalgia. Seen as a depiction of a strong, traditional, and reserved woman, Whistler’s Mother appeared to several generations of Americans to embody the virtues of motherhood. As views of motherhood evolved later in the century, the painting was sometimes interpreted as representing a rather distant, perhaps even overbearing, matriarch. Like many icons of art, it has also served as fodder for political causes, advertising campaigns, and increasingly outrageous parodies.

COMING HOME: WHISTLER’S MOTHER IN AMERICA

Whistler’s Mother was exhibited in Philadelphia and New York in 1881 and 1882, but it did not gain widespread popular attention in America until 1932. In that year the French government permitted the painting to travel to the United States in an effort to improve public opinion of France in America. The loan was organized by the newly opened Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which made the painting a centerpiece of the exhibition American Painting and Sculpture, 1862–1932. The presence of Whistler’s famous portrait helped the exhibition draw more than 50,000 visitors in the first six weeks, saving the fledgling museum from financial difficulties. In mid-December, the museum asked the French government to extend the loan and allow the painting to travel to other museums around the United States.

Over the next eighteen months, Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1 traveled to venues in eleven cities before returning to New York for a final showing. At each stop, men, women, and children lined up to see it. Spirits were low as the American people continued to struggle with financial instability during the Great Depression. Headlines across the country noted the painting’s immense monetary value (claimed to be one million dollars), and heightened security measures were put in place to protect the work.

A MODERN MASTERPIECE

When Alfred Barr, then director of the Museum of Modern Art, thought of bringing Whistler’s portrait to the United States, he imagined not only a successful exhibition but also the celebration of an American modernist painter. The work, he argued, was not primarily an homage to motherhood, but rather a quintessential example of early modern art. In his book What is Modern Painting?, Barr illustrated this point with a diagram depicting the painting’s compositional structure without the figure. The result is an abstract design, as Barr stated, “not very different” from the purely nonrepresentational work of Piet Mondrian.

Whistler may very well have appreciated Barr’s interpretation of the painting. As he had argued in 1890, “The vast majority of English folk cannot and will not consider a picture as a picture, apart from any story it may be supposed to tell... Take the picture of my mother, exhibited at the Royal Academy as an ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black.’ Now that is what it is. To me it is interesting as a picture of my mother; but what can or ought the public do to care about the identity of the portrait?”

THE STAMP

While Whistler and Barr insisted on viewing the portrait as an aesthetic arrangement first and foremost, the American public and press saw it primarily as an image of motherhood. Toward the end of the painting’s tour of the United States in 1934, a commemorative stamp of the painting was issued with the words “In memory and in honor of the mothers of America.” Made specifically for Mother’s Day and circulated nationally, the stamp featured a cropped composition with an added bouquet of flowers.

MOTHERHOOD AND AMERICAN CULTURE

Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1 proved to be a powerful, enduring image of American motherhood. It has been used in advertisements and political ads and referred to in other works of art. In 1938 the town of Ashland, Pennsylvania unveiled a statue in honor of motherhood and used Whistler’s painting as its direct point of reference. During the Great Depression, the painting came to represent the values of honor, stability, and even patriotism. This iconic status resonated with the public, who saw Anna Whistler as a symbol of American strength and a source of national pride.

During the mid-twentieth century, the painting was often interpreted as representing a more domineering or stern female persona. This shift may reflect the changing perception of motherhood from the proper Victorian matriarch of the 1870s to the warmer, more caring “homemaker” of the 1950s and ’60s to the multitasking working mother of the 1980s onward.

POPULAR CULTURE

The portrait of Anna Whistler has been reproduced and manipulated throughout popular culture, particularly in print and film. In the 1930s and ’40s, the image was used in posters for war bonds and temperance leagues. For Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho, designer Saul Bass composed the final scene as a stark shot of Norman Bates in profile, mimicking the configuration of the painting. Hitchcock decided to have Bates facing the camera instead, though the other compositional elements remained intact.

The painting was and continues to be used as a motif for greeting cards, magazine covers, political cartoons, television episodes, advertisements, and motion picture scenes. The iconic status of the work has sparked a wide range of parodies, from a New Yorker magazine cover illustration of an angry mother waiting for the phone to ring on Mother’s Day to more alluring imitations of her pose to sell household items such as window blinds. Though the imitations of Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1 have ranged from serious to absurd, the painting has had an enduring legacy in American visual culture for more than a hundred years.