Drawing as Document

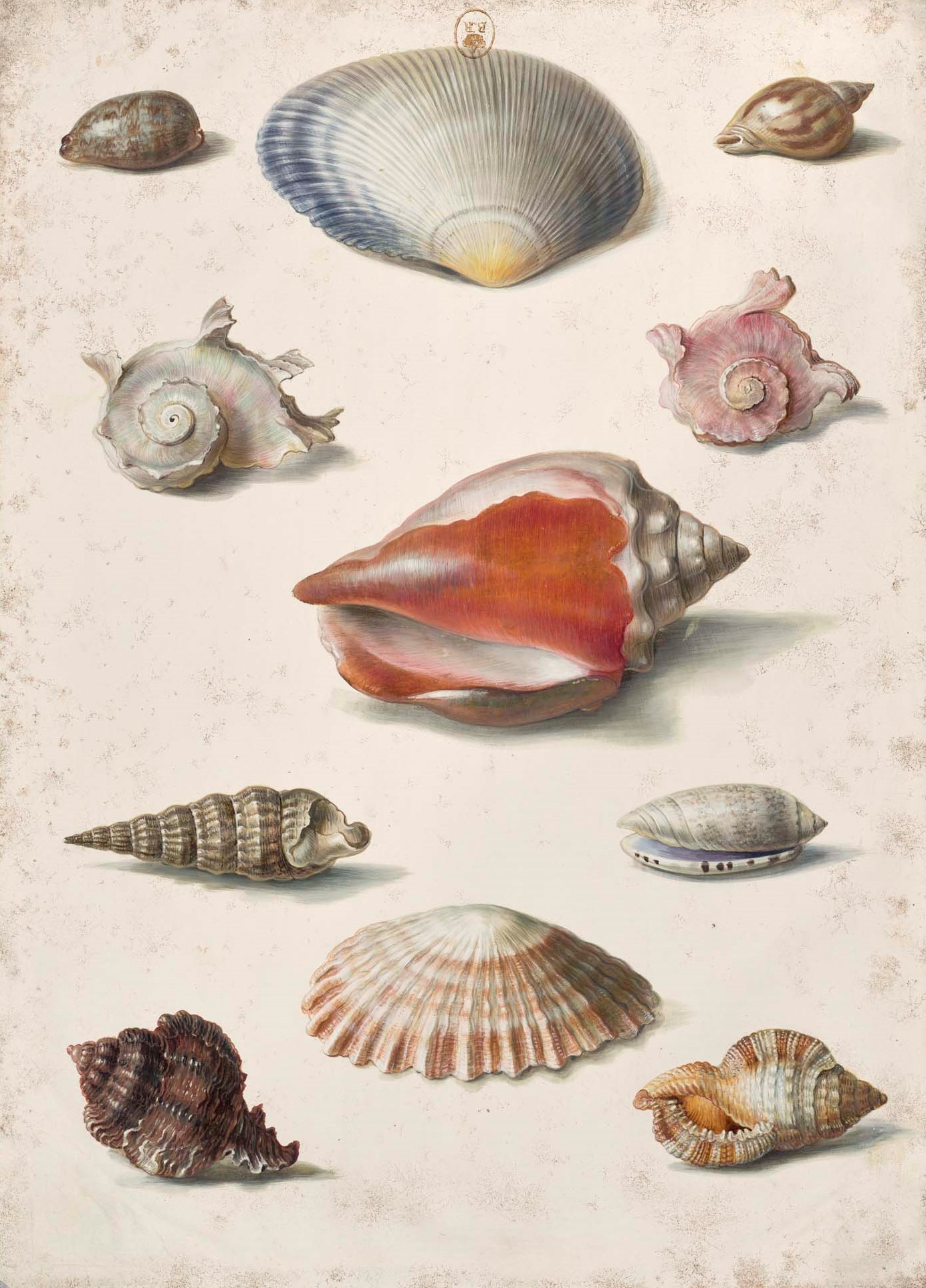

-BOITE-ECU_Coquillages-ESTNUM-2021-2978.jpg) Émilie Bounieu (French, 1768–1831), Shells, 1792–95. Gouache on vellum, 11 1/8 × 8 1/4 in. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RÉSERVE B-6 (E, 6) BOÎTE FOL

Émilie Bounieu (French, 1768–1831), Shells, 1792–95. Gouache on vellum, 11 1/8 × 8 1/4 in. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RÉSERVE B-6 (E, 6) BOÎTE FOLThe drawings in this exhibition offer a vital link to events and issues of eighteenth-century France, from the extraordinary to the everyday. In many of the examples here, artists were not working in an official capacity but independently recording what they observed. They took up their drawing tools to document urban spectacles like diplomatic visits, festivals, and hot-air balloon launches, as well as the convulsions of political change and revolutionary violence. Among more commonplace events, art sales, street vendors, and period fashions also attracted artists’ interest and became immortalized for future generations. Additionally, drawing proved an ideal medium for illustrating diverse natural history specimens in meticulous detail. By the end of the eighteenth century, the technique had so thoroughly proved its documentary value that an entire team of artists and engineers proficient in drawing was drafted to Napoleon Bonaparte’s military expedition in Egypt to illustrate the desirability of their conquest.

Description de l’Égypte

Jean-Marie-Joseph Coutelle (French, 1748–1835), Collection of Antiques, Painted Fabrics, and a Wooden Mask, 1798–1817. Watercolor and graphite, 11 5/8 × 17 1/4 in. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RÉSERVE UB- 181 (F BIS)-FT 4, MFILM M-23965

Jean-Marie-Joseph Coutelle (French, 1748–1835), Collection of Antiques, Painted Fabrics, and a Wooden Mask, 1798–1817. Watercolor and graphite, 11 5/8 × 17 1/4 in. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RÉSERVE UB- 181 (F BIS)-FT 4, MFILM M-23965

In 1798, General Napoleon Bonaparte attempted to cut off Britain’s overland trade route with India by seizing control of Egypt. Accompanying him on this military expedition were over 150 scholars—mostly engineers—whose mission was to document every aspect of Egypt, from its antiquities to its natural wonders and modern-day residents. While the French eventually evacuated in 1801 after their defeat at the hands of British and Ottoman forces, they returned with nearly a thousand drawings that would form the basis of the Description de l’Égypte (Description of Egypt, 1802–1822), a twenty-three-volume compendium encyclopedic in its ambitions. A fundamental purpose of the state-sponsored publication was to legitimize Napoleon’s imperialism through a display of French intellectual prowess, and through a depiction of Egypt as a territory worth annexing due to its rich history. In the abundance of details they archive, images of the Description of Egypt suggest that Napoleon’s academic emissaries saw themselves as valiantly preserving (rather than violently pillaging) a civilization in decline. While recording eroding pharaonic monuments for posterity, the draftsmen depicted the country’s living citizens with an ostensible ethnographic precision inflected with subjective pathos. This cache of drawings, housed at the BnF since 1829, is at the origin of two powerful cultural constructs that defined how Europe imagined the Eastern world: the field of Egyptology, and the Orientalist mode of (mis)representation in art and literature.