JAPONISME

Beginning in the 1850s, exchange between the Tokugawa shogunate in Edo Japan and the rest of the world started to expand beyond the mostly Dutch merchants who had been permitted to live on the artificial island of Dejima off the coast of Nagasaki. Partly as a response to American efforts to force Japan to sign the Harris Treaty, which gave the United States control over tariffs and forced the opening of additional ports for foreign commerce, domestic tensions in 1868 triggered the downfall of the Tokogawa shogunate. The following period, the Meiji Restoration, led to Japan’s active engagement with the community of global empires, which enabled a wider appreciation of Japanese art and design, particularly by American and European audiences. The neologism japonisme was coined by French art critic Philippe Burty in 1872 to describe the popularity and influence of these artistic imports.

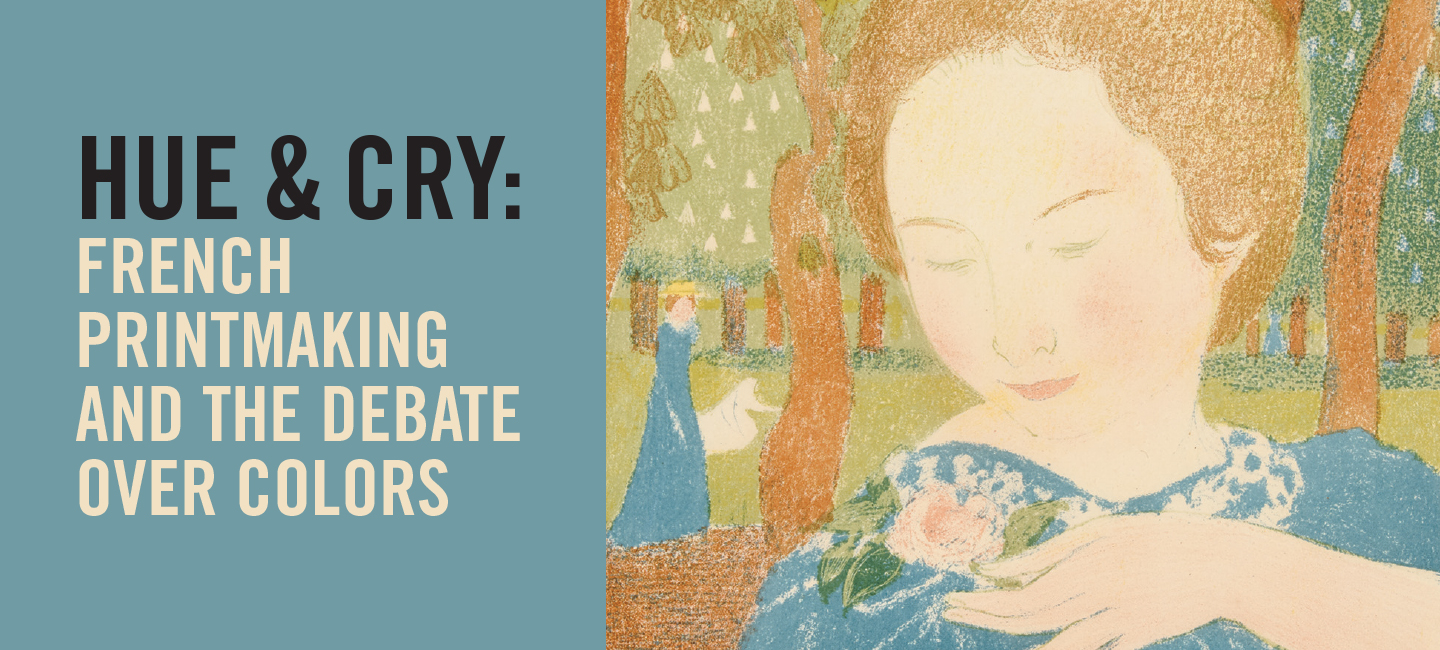

The impact of Japanese aesthetics diffused throughout the visual and material culture of Europe, touching the fields of architecture, fashion, ceramic, landscaping, and the fine arts. The influence of earlier ukiyo-e woodcuts—relief prints known for their lack of one-point perspective, flattening of planar dimensions, use of negative space, asymmetrical compositions, and, above all, vibrant use of color—inspired both painters and printmakers. The taste for ukiyo-e prints was rampant throughout the second half of the nineteenth century; in Paris alone, these prints were featured in exhibitions in 1867, 1887, and 1890. Many artists who appreciated Japanese prints were also collectors but opted to execute their own japonisme-inspired designs in intaglio or planographic printmaking mediums.