June 11–October 10, 2016

Spanish Kings and Sites of Display

Habsburg Kings of Spain, 1516–1700

Charles I, r. 1516–56: Charles was also Holy Roman Emperor (known as Charles V in that succession). Abdicated the Spanish crown in favor of his son;

Philip II, r. 1556–98: Upon his death, his son;

Philip III, r. 1598–1621: Upon his death, his son;

Philip IV, r. 1621–65: Upon his death, his son;

Charles II, r. 1665–1700: The last of the Habsburg line to rule Spain.

Bourbon Kings of Spain, 1700–1868

Philip V, r. 1700–1724: Son of the Grand Dauphin of France and great-grandson of Philip IV, abdicated in favor of his son;

Louis I, r. 1724: Ruled until his death eight months later; upon his death, the crown reverting to his father;

Philip V, r. 1724–46: Upon his death, his son;

Ferdinand VI, r. 1746–59: Upon his death, his brother;

Charles III, r. 1759–88: Upon his death, his son;

Charles IV, r. 1788–1808: Abdicated in favor of his son;

Ferdinand VII, r. 1808: Reign interrupted by the Napoleonic invasion, then restored;

Ferdinand VII, r. 1813–33: Upon his death, his daughter;

Isabella II, r. 1833–68.

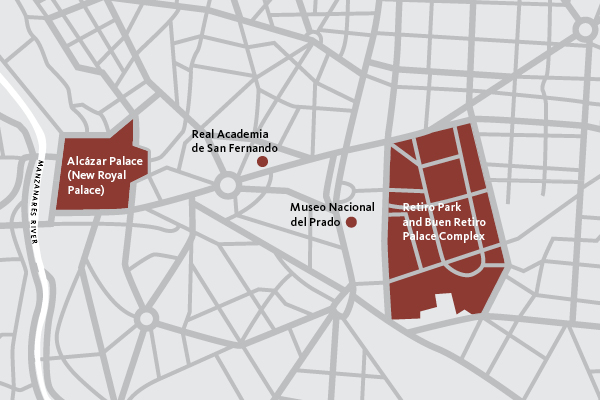

Alcázar Palace

Philip II adopted this castle as the official residence of the Habsburg monarchy after moving the court from Toledo to Madrid in 1561. Built on the grounds of a former Moorish fortress dating from the ninth century, the Alcázar was expanded by successive Habsburg kings until it was destroyed by fire in 1734. It was replaced soon after by the New Royal Palace of Madrid.

Buen Retiro Park and Palace

As Madrid grew throughout the seventeenth century, Philip IV ordered the construction of this royal palace and garden complex at the capital’s eastern edge. Within the Buen Retiro Palace—largely razed during the Peninsular War of 1808–14—was the fabled Hall of Realms, adorned with royal portraits, monumental battle paintings, and allegories of princely virtue by living artists such as Jusepe de Ribera, Peter Paul Rubens, Diego Velázquez, and Francisco de Zurbarán.

Museo Nacional del Prado

Ferdinand VII and his wife, María Isabel de Braganza, oversaw the establishment of the Real Museo de Pinturas, today known as the Museo Nacional del Prado. Housed in the former Natural History Cabinet, the museum opened to the public in 1819. The Prado’s sala reservada was created in 1827 to display nudes in the royal collections, but by 1838, these works were integrated into the main galleries.

Real Academia de San Fernando

Philip V founded Spain’s first royal art academy in 1744. When his son Charles III attempted to purge the Spanish Royal Collections of nudes in 1762, the court painter Anton Raphael Mengs and the statesman Leopoldo de Gregorio, Marquis of Esquilache, intervened to protect the paintings. By the 1790s, works deemed indecent were sent to the Real Academia for limited viewing by artists.

Royal Palace of Aranjuez

This favorite royal pleasure palace was conceived by Charles I, begun by his son Philip II, and modernized by subsequent generations of Habsburg and Bourbon monarchs. The elaborate gardens of Aranjuez were particularly prized and came to include canals, fountains, statues, and an arboretum.

Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso

Spain’s first Bourbon monarch, Philip V, modeled La Granja de San Ildefonso on Versailles, but as a private residence for use upon his abdication in 1724. Though the unexpected death of his son and successor soon returned Philip to the throne, La Granja would remain this king’s favorite retreat throughout his life.

San Lorenzo de El Escorial

Conceived by Philip II as a monastery, the Escorial expanded throughout the late sixteenth century to include a royal residence and mausoleum, as well as a basilica, college, and library. Along with the Alcázar, this austere complex outside of Madrid contained the greatest number of artworks in the collections of the Spanish Habsburgs.

Torre de la Parada

Almost one century after Philip II built this hunting lodge on the grounds of the Palace El Pardo in 1547, his grandson Philip IV entirely transformed its interior. Throughout the 1630s, Philip IV installed in this building more than a hundred landscapes and mythological scenes from Rubens’s workshop as well as court portraits by Velázquez.

Prado Nomenclature

The Prado has had several official names over time: 1819–39: Real Museo de Pinturas; 1839–68: Real Museo de Pintura y Escultura; 1868–1920: Museo Nacional de Pintura y Escultura; and 1920–present: Museo Nacional del Prado. This exhibition uses time period-specific names where appropriate but uses “Museo Nacional del Prado” to refer to the institution generally.

The shaded areas of this map show the lands under Spanish Habsburg control around 1580 and illustrate the vast and varied expanse of the Habsburg empire, which also extended to the New World.

Community of Madrid

Madrid City Center

The rectangles indicate the area of the map above but are not to scale.

A fully illustrated catalogue accompanies the exhibition, with an essay by Javier Portús on the Spanish royal taste in collecting and the role of the sala reservada, as well as a contemporary response to understanding the nude in Renaissance and Baroque painting by Jill Burke. The catalogue is published by the Clark and distributed by Yale University Press. Call the Museum Store at 413 458 0520 to order.