FEBRUARY 28–May 17, 2015

ABOUT THE artists

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson

English, 1889–1946

1917

Photograph by Malcolm Arbuthnot

Known for his bleak and graphic depictions of World War I, C. R. W. Nevinson worked as a painter and printmaker throughout his career. Nevinson began his artistic training in 1908 at St. John’s Wood School of Art, and enrolled at the Slade School of Fine Art in London the following year. His visit to the Sackville Gallery’s 1912 Futurist exhibition inspired him to start working in that manner. His connection with the Italian Futurists and especially their leader, the poet and editor Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, was cemented with their jointly written manifesto, “Futurism and English Art” (1914). But in marked contrast to the Futurists’ heroicizing approach to World War I, Nevinson increasingly utilized this style to capture the war’s horror and devastation. As an ambulance driver for the Red Cross and, later, as an official war artist for the British government, Nevinson developed a visual vocabulary focused on military combat and its aftermath. Abandoning Futurism in 1919, Nevinson concentrated on naturalistic urban scenes until ceasing his printmaking practice in 1932. His autobiography, Paint and Prejudice, was published in 1937 as a memoir primarily of his experiences as an artist during the Great War.

Edward Wadsworth

English, 1889–1949

1916

Photograph by Alvin Langdon Coburn

Edward Wadsworth grew up in Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire, an industrial town in northern England. While an engineering student in Munich from 1906 to 1907, Wadsworth took art classes at the Knirr School. In 1907 he returned to England, studying at the Bradford School of Art before receiving a scholarship in 1909 to attend the Slade School of Fine Art. At the Slade, Wadsworth met British proponents of Futurism, such as fellow artist Wyndham Lewis, with whom he founded the Vorticist movement in 1913 and the Rebel Art Centre in 1914. During World War I, Wadsworth worked as a naval intelligence officer before returning to England as a designer for the dazzle camouflage campaign. In this campaign, vibrant abstract designs were applied to British merchant ships to confound and ward off attacks from German U-boats. The campaign was ultimately short-lived, for while the bold designs made the ships’ size, speed, and orientation difficult to determine, the patterns needed frequent repainting due to the deteriorating effects of salt water. Around this time, Wadsworth experimented with lithography and etching, in addition to woodcut and oil painting. From 1913 until 1921, Wadsworth created more than fifty woodcuts on various themes; however, in early 1927 he burned all of his blocks, stating, “They’re finished and done with.” Later that year, he moved from London to the Sussex countryside. Living in Sussex, Wadsworth became involved with other artistic groups, such as Abstraction-Création and Unit One. His reputation remained strong until the end of his life; among other accolades, his works were selected for the Venice Biennale in 1940, and he became an ARA (Associate Member of the Royal Academy) in 1943.

Andrew-Power

Sybil Andrews

English, 1898–1992

Cyril Power

English, 1872–1951

The close artistic relationship between Sybil Andrews and Cyril Power began in 1921, when Andrews and Power met in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk, England. Their move to London the following year solidified the connection between the two artists, with both enrolling in the Heatherley School of Fine Art. Working together at this time, the pair wrote a manifesto entitled “Aims of the Art of To-Day” (1924), focusing on art in relation to modern urban life. Both then assumed positions at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, where they met Claude Flight and immersed themselves in the production of linocuts. Beginning in 1930, the pair shared a studio, located at 2 Brook Green, in the Hammersmith district of London. Also around this time, they adopted the pseudonym “Andrew-Power.” It was under this name that the artists completed a series of posters commissioned by the London Underground, advertising events accessible via public transportation. Though the commission was originally given to Power, it was largely realized by Andrews. Regardless of the distribution of work, the two were significant influences on each other, utilizing similar strategies in their handling of modern subject matter, along with a similar palette. The Redfern Gallery exhibited works by Andrew-Power in 1933. The pair’s relationship, characterized by Andrews as strictly professional, ended in July 1938, when they disbanded their joint studio practice and Power returned to his wife and children in Surrey.

Sybil Andrews

English, 1898–1992

1947

Glenbow Archives, Calgary, PA-3376-1-34

Sybil Andrews began her artistic training in 1918 after returning home to Bury St. Edmunds from her role as a welder on Bristol Fighter planes during World War I. Following the completion of a correspondence art course, she worked under the tutelage of Cyril Power. In 1922, Andrews and Power relocated to London, enrolling in the Heatherley School of Fine Art. Her interest in block printing developed at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, where she served as its first secretary from 1925 until 1928. Leaving the school in 1928, Andrews established and maintained a studio with Powers until departing for a simpler life in southern England in 1938. During World War II, she stopped producing linocuts while she worked in a shipyard. In 1947, seeking a fresh start in the aftermath of the war, Andrews and her husband immigrated to Campbell River, British Columbia, where she became a Canadian citizen. She resumed her linocut practice in 1951.

Margaret Barnard

Scottish, 1898–1992

1930

Drawing by Robert Austin © Estate of Robert Austin, RA

Photo courtesy Rye Art Gallery, UK

Beginning her artistic training at the Glasgow School of Art, Margaret Barnard participated in her first exhibition there in 1922. After living in Italy and then Glasgow with her fellow artist and husband, Robert Mackechnie, Barnard moved to London in the mid-1920s. There, she enrolled in the Grosvenor School of Modern Art. During her short tenure at the Grosvenor School, Barnard mainly studied the art of linocut with Claude Flight. Around this time, her works—which included landscape paintings as well as linocuts—found a fairly significant following, leading to multiple exhibitions at such venues as the Royal Academy. In 1934, she and Mackechnie settled in Rye, Sussex. She continued working up until the Second World War, mainly designing posters for the London Underground. During the war Barnard stopped producing art, only to resume painting after her husband’s death in 1975.

Claude Flight

English, 1881–1955

c. 1925

Courtesy Michael Parkin Gallery, London

Claude Flight worked in a variety of capacities—as a librarian, an engineer, a farmer, and a beekeeper—prior to beginning his artistic training at the Heatherley School of Fine Art in 1912. He left the school during the First World War, serving as a captain in the British Army. Returning to his artistic practice after the war, and now influenced by C. R. W. Nevinson and the Futurist ideals he had encountered at Heatherley’s, Flight began creating linocuts in 1919. His association with the Grosvenor School of Fine Art started in 1926, when he became a teacher of linocut. Flight went on to become a major proponent of the medium, appreciating its conduciveness to handling modern themes, such as the speed and dynamism of metropolitan life. Flight’s commitment to the technique is reflected in his organization of annual linocut exhibitions from 1929 to 1937, the publication of two books on linocut (in 1927 and 1934), and his continual advocacy for the medium during his tenure as editor of the journal Arts and Crafts Quarterly (1926–27). His belief that art should correspond to modern life, and his view of linocut as a democratic medium ideally accessible to all, were taken up in earnest by his students, including Dorrit Black and Edith Lawrence. Flight and Lawrence had a lifelong personal and working relationship, beginning when they first met in 1922. They lived together soon after, summering in Flight’s neolithic cave in Chantemesle, forty miles outside of Paris, and spending the rest of the year in London. In 1943 their London home, including all of Flight’s paintings and printing blocks, was destroyed in the wartime bombing of the city. The couple subsequently moved to Donhead St. Andrew, where Flight and Lawrence lived until Flight’s death in 1955.

William Greengrass

English, 1896–1970

c. 1920

Courtesy Michael Parkin Gallery, London

William Greengrass had some artistic training prior to enrolling in the Grosvenor School of Modern Art in 1930. While his pre-Grosvenor works consist primarily of wood engravings, his studies with Claude Flight propelled him toward an embrace of the color linocut. Similar to Flight, Greengrass focused on scenes of speed and movement. His works were exhibited alongside those by other Grosvenor School artists in Flight’s exhibitions at the Redfern Gallery, and in Flight’s two linocut manuals. Not much is known about Greengrass outside of his work at the Grosvenor School, other than the fact that he was a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Cyril Edward Mary Power

English, 1872–1951

c. 1916–18

Cyril Power initially trained as an architect in his father’s London-based firm. He was gifted and highly sought after, receiving commissions and accolades for his building designs. Starting in 1909, Power studied architectural history, publishing A History of English Medieval Architecture in 1912. From 1916 until the end of the First World War, Power served in the workshop of the Royal Flying Corps. In 1918, after demobilization, he moved with his young family to Bury St. Edmunds. It was there that he met Sybil Andrews in 1921. Leaving his wife and children behind, Power moved to London with Andrews in 1922 to attend the Heatherley School of Fine Art; there, they became acquainted with C. R. W. Nevinson and his Futurist inspired work. After leaving Heatherley’s, Power taught the principles of modern architecture and ornament at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art from 1925 until 1928. In 1938, he abandoned his London art practice and returned to his family in Bury St. Edmunds. During World War II, he worked as a surveyor alongside a heavy rescue squad. In the aftermath of the war, he ceased his printmaking practice, focusing on landscape painting and floral studies until his death in 1951 at age seventy-nine.

Lill Tschudi

Swiss, 1911–2004

1933

It was Lill Tschudi’s viewing of linocut animal prints by the Austrian artist Norbertine Bressern-Roth that inspired Tschudi to pursue printmaking when she was just eighteen years old. In 1929, Tschudi enrolled at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art after seeing an advertisement for the school in The Studio magazine. At Grosvenor, she studied with Claude Flight—an experience that, although brief (six months), was nonetheless of long-lasting significance. Her subject matter, which included themes related to sports and urban life, followed Flight’s own dedication to modern subjects, and her devotion to the technique of handprinting corresponded with her teacher’s working process. Tschudi continued her art studies in Paris from 1931 until 1933 with artists that included Fernand Léger, André Lhote, and Gino Severini. During this period, she remained close with Flight, who used her prints as illustrations in his textbooks on linocut. At the outbreak of World War II, Tschudi returned to Switzerland and served in the Women’s Aid Service. After the war, Tschudi settled in her hometown of Schwanden, where she resumed her artistic practice, working in a gestural, abstract style until her death at age ninety-three.

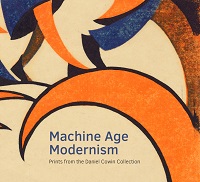

Machine Age Modernism is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with essays by Jonathan Black, a senior research fellow in the history of art at Kingston University in London, and Jay A. Clarke, Manton Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs at the Clark.