ABOUT THE ARTIST

Paul Goesch

Photographer unknown, Portrait of Paul Goesch (detail), c.1920. Collection: Freundeskreis Paul Goesch e.V., Cologne.

Photographer unknown, Portrait of Paul Goesch (detail), c.1920. Collection: Freundeskreis Paul Goesch e.V., Cologne.

Born in 1885 in the city of Schwerin, Paul Goesch spent his childhood in Berlin. Though baptized Lutheran, he became devoutly Catholic in his teens, “overwhelmed,” as he recalls “by the stunning splendor of the church.” Goesch performed poorly in school, suffered chronic illness, and was isolated from his classmates, retreating into himself. Still, tutored by an older student, he developed a love of art and literature, as well as architecture—which he went on to study.

At the age of twenty-four, intrigued by the new possibilities of Freudian psychoanalysis, Goesch began a session during which he experienced his first psychic break, and entered a sanatorium for treatment. Returning to Berlin a year later, he received a diploma as a state construction foreman, a position in which he worked only briefly. Goesch’s curiosity about the world led him to theosophy and the teachings of Rudolf Steiner, with their focus on the connections between the outer, natural world and the inner spiritual one. He joined Steiner’s Anthroposophical Society in 1913 and took part in building its headquarters, the first Goetheanum, in Dornach, Switzerland—one of the most significant expressionist structures yet to be realized.

During the First World War, Goesch worked as a civil servant in the post office before again being institutionalized from 1917 to 1919 with the diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. Upon his release, Goesch lived for two years in Berlin, during which time he was a member of the Work Council for Art, the November Group, radical organizations with socialist aims, and the Glass Chain, an ongoing correspondence between modernist architects. In 1920, the prestigious Galerie Flechtheim in Dusseldorf, which counted Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Pablo Picasso among its artists, featured Goesch’s work. By July 1921, however, Goesch was again institutionalized, as he would remain, with brief interruptions, for the rest of his life.

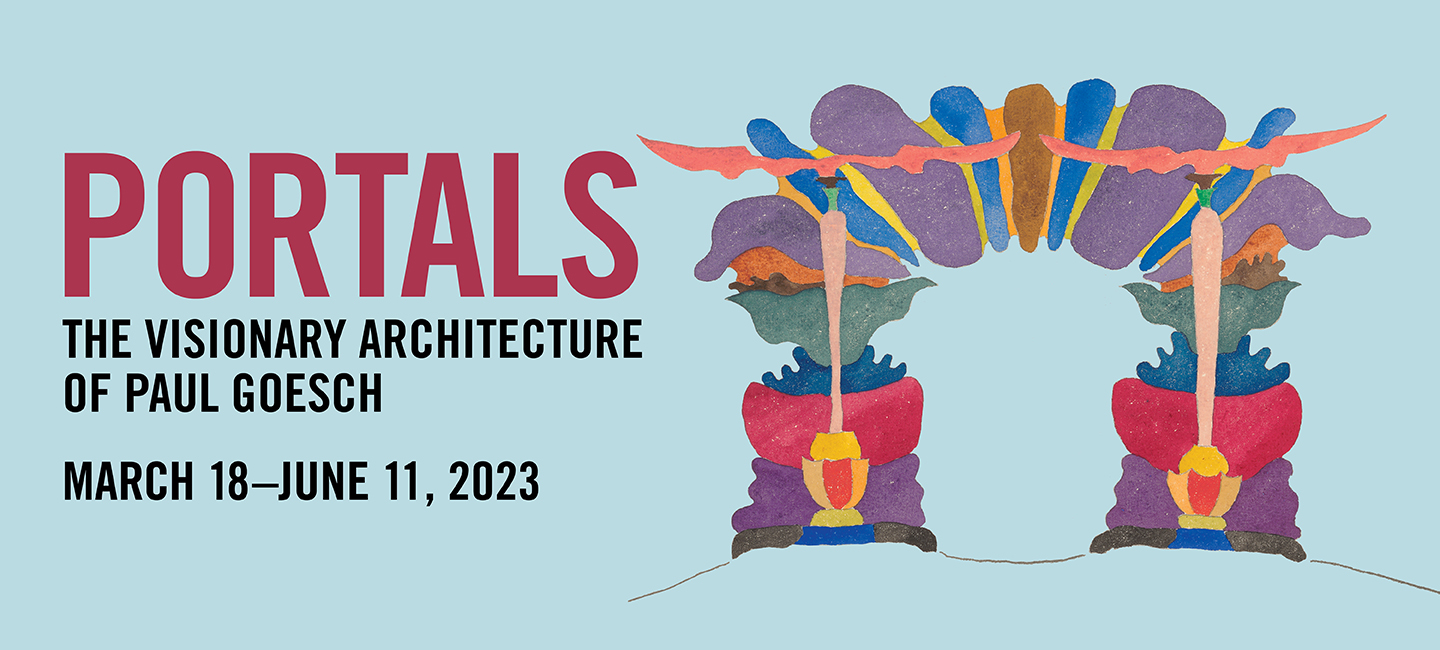

Most of the drawings in the exhibition were made during Goesch’s two years in Berlin, outside institutions. Some suggest commemorative arches or entryways. Others evoke architectural canopies, like the kind that cover alters in churches or thrones in palaces, expressing a divine or royal presence. Still others depict the facades of chapels, whose ornamental entries traditionally mark the transition from a profane to a sacred realm. While Goesch’s drawings vary greatly in style and technique, and are ambiguous in scale and suggested material, they are metaphysically rich in their suggestion of passages to another state—whether holiness, enlightenment, or utopia.

The conditions that enabled Goesch’s moment in the sun lasted only briefly. In 1919, Walter Gropius —a co-founder of the Work Council for Art and a member of the Glass Chain—founded the Bauhaus, a school dedicated to uniting the arts and crafts under the sign of architecture. While the school began with a quasi-mystical, expressionist character, inspired by the guild-based collaboration of Gothic artisans, by 1923, under the influence of Soviet constructivism, it committed itself to “a new unity” between art and technology. As the hyperinflationary Weimar Republic’s currency stabilized in the same years, a sober and scientiftic functionalism took hold and glass and steel structures sprouted up across Germany. In 1925, Gustav Hartlaub, director of the Mannheim Kunsthalle—who five years earlier had acquired Goesch’s drawings for his museum—would popularize the term Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) to describe a matter-of-fact, post-Expressionist tendency in art, with clear parallels in architecture. Expressionism, by this time, had run its course.

Yet these years of high modernism were also short-lived. Following its rise in 1933, the Third Reich either crushed or coopted various strains of the avant-garde, with dire consequences for artists and architects—and especially those deemed ethnically, sexually, or psychologically aberrant. Goesch’s work appeared in the 1937 touring exhibition Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art), along with many of his expressionist peers. After years of institutionalization, in 1940, Nazi doctors murdered Goesch in the former Brandenburg prison as part of the “Aktion T4” involuntary euthanization program. The regime would also murder some 300,000 other patients with mental illness, whom they designated as “life unworthy of life.” Under fascism, Goesch’s ungovernable visions became untenable; on paper, his unique way of building remains.