The Glass Chain

Hermann Finsterlin, Formal study, 1920, graphite and watercolor, with some gouache. Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, DR1988:0260

Hermann Finsterlin, Formal study, 1920, graphite and watercolor, with some gouache. Centre Canadien d'Architecture/Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal, DR1988:0260© Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In the aftermath of the war, ambitious building in Germany was impossible amidst material shortages, a hyperinflationary currency, and a lack of commissions. Under these conditions, the practical, physics-bound work of architecture was replaced by the speculative fantasies of “paper architecture,” in which anything was possible. Architecture assumed a leading place in Expressionist circles in these years: the Work Council for Art was co-founded by architects Walter Gropius and Bruno Taut and guided by architectural metaphors. Taut agitated for public funding for experimental architecture and workers’ housing, the dissolution of the art academies, and the “destruction of artistically valueless monuments”—to free up building material. He and his peers dreamt of formally inventive houses for the people that broke from the classical styles and elitist social structures of the past.

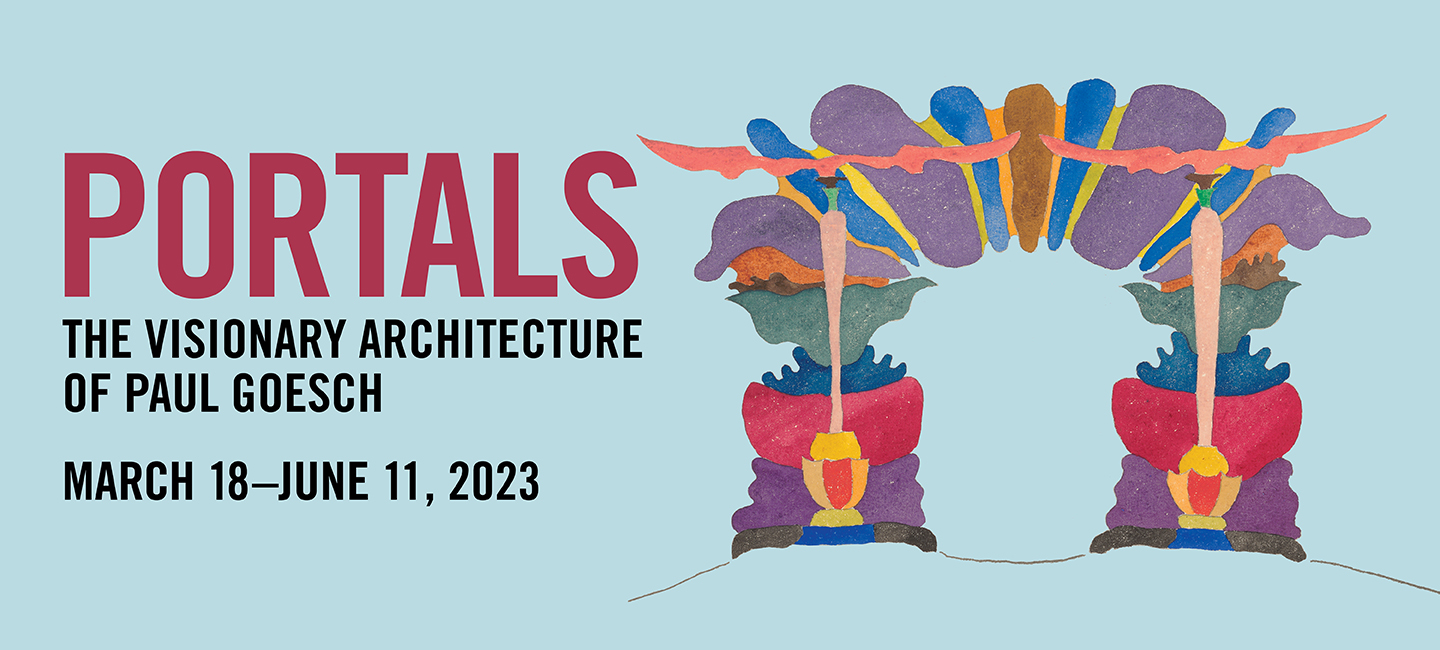

Disappointed by a lack of political agency in the new government, Taut took his activities underground, establishing in 1919 a group of architects around Germany who corresponded via pseudonyms about the building of the future, sending each other theoretical texts and drawings by mail. Named the Gläserne Kette (Glass Chain), in homage to the material many of them favored in their schemes, the group included twelve other architects, Paul Goesch among them. Some of the members went on to build signature modernist buildings in the years to come, such as Walter Gropius, Hans Scharoun, and Taut himself, while others became known for their unbuilt fantasies, such as Hermann Finsterlin. Despite its secretive posture, much of the group’s theoretical and artistic output appeared in Taut’s journal Frühlicht (Dawn). Goesch was a highly valued contributor; in addition to his texts, more drawings by him appear in Taut’s journal than by most any other member of the group.