Expressionism in Germany

Käthe Kollwitz, Memorial sheet for Karl Liebknecht, 1920, woodcut on paper. The Clark, 2010.1

Käthe Kollwitz, Memorial sheet for Karl Liebknecht, 1920, woodcut on paper. The Clark, 2010.1Expressionism began in the first decade of the twentieth century as an attempt to create a new art for the future and escape the stifling culture of Imperial Germany under Kaiser Wilhelm II. The young artists who formed associations like Die Brücke (The Bridge) in 1905 and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) in 1911 preferred bright colors and distorted, dynamic forms. They looked inward, outward, and back for alternatives to academic conservatism: inward, to their emotions and subjectivity; outward, to the arts of Africa and Oceania that they saw in museums; and back, to medieval Germany, for its mysticism and tradition of woodcuts. Indeed, printmaking was a popular medium of artistic experimentation given its affordability of production and distribution and its graphic, emotional immediacy.

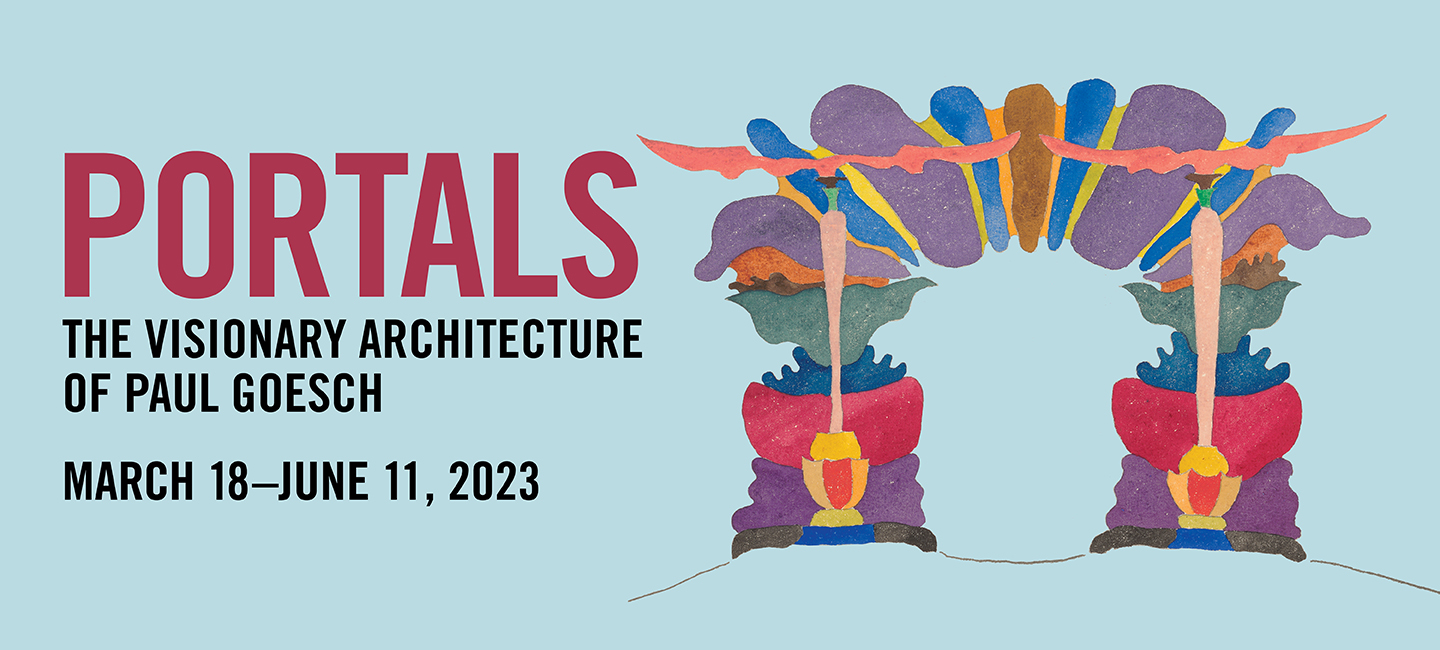

A “second generation” of Expressionists, on view in this exhibition, continued their work in the Weimar Republic (1918–33). Responding to the unthinkable horrors of the war, in which many of them served, and the deprivation in its wake, this art took a darker turn but was also, for many, more political—intent on building a new social order. In the spirit of the November Revolution that birthed the Weimar Republic, artists and architects formed radical associations with socialist aims: the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Work Council for Art) and Novembergruppe (November Group) sought a voice for art workers in the new government and were largely guided by architects and the utopian metaphors of architecture (Paul Goesch was a member of both). While their hopes for political agency were soon disappointed, their radical aesthetics continued.