July 4–October 10, 2016

the settlement of williamstown and stone hill, 1750-1855

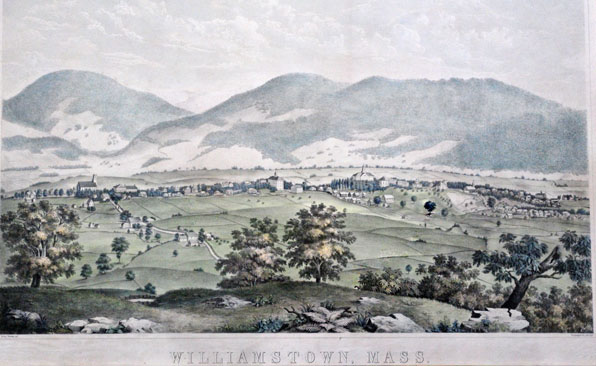

George Yeomans, (American, 1833–1895), Printed by P.S. Duval Co, Philadelphia, PA, Williamstown, Mass. As seen from Stone Hill (detail), 1855–56. Hand-colored lithograph, 15 3/8 x 26 in. (39.1 x 66 cm). Flynt Family Collection

While Native American Mahicans no doubt traversed Stone Hill on their journeys to and from their settlements in the Hudson and Connecticut River Valleys, to date there has been no evidence found of Native American settlement on Stone Hill itself. The first recorded encounters with the landscape came from colonists, who gave the hill its name during the mid-eighteenth century. These early settlers “improved” the land by clearing much of the hill’s forests to create fields for farming and meadows for grazing sheep and cattle. The remaining woodlots provided timber and fuel for the local economy into the early twentieth century. Remnants of these woodlots can still be found on the hill, along with stone fences demarcating abandoned fields and pastures. The peak of agricultural use of the land came around 1830, after which second-growth forests began to reclaim former farmlands. This process accelerated after World War II, when tractors replaced horses and oxen in farm work, allowing the conversion of feed crop acreage to other uses. Early deed records and maps allow us to reconstruct how the land use on and around Stone Hill has changed over time.

Yeomans Engraving

The lithograph pictured depicts Williamstown in 1855, when the area was largely farmland punctuated by a few college, town, and church buildings. George Yeomans was a Williams College undergraduate who published this work the year he graduated from college. The view is from Stone Hill, which remains to this day the primary location for an overview of the town. As the original road linking Pittsfield, Massachusetts to Bennington, Vermont via Williamstown ran directly over Stone Hill, visitors on horseback, in carriages, and later in automobiles would have been able to enjoy this vantage point as they traversed Stone Hill Road. Today’s visitors can venture on foot to experience this same view.

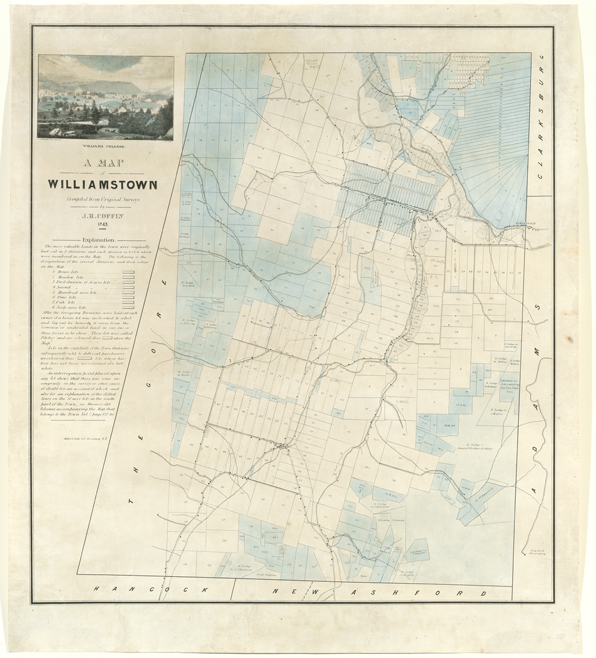

Mills Map

John Mills, Map of Williamstown, 1830. 22 1/2 x 28 1/4 in. (57.2 x 71.8 cm). Massachusetts Archives, Boston, Massachusetts

In 1830 the Commonwealth mandated the mapping of every town in Massachusetts, showing woodlots, cleared land, water sources, meeting houses, and municipal structures. The map above is a reproduction of the map made for Williamstown by local lawyer, selectman, and surveyor John Mills (1787–1839); the original resides in the State Archives in Boston. Its careful construction makes it a primary source for the interpretation of Williamstown’s environmental history. Tan areas indicate land cleared for agricultural use between 1750 and 1830; brown washes along the Hoosic and Green Rivers indicate marshy wetland vegetation; green areas represent the residual forests and woodlots; and stipples indicate elevation. Stone Hill is labeled near the center of the map.

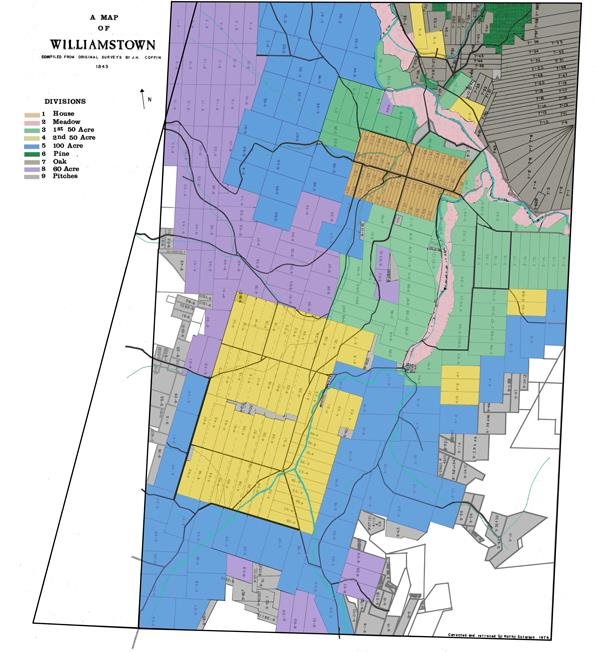

Coffin Map

James Henry Coffin map, 1843 (left), based on information from 1750. Image courtesy of Boston Rare Maps, Southampton, Massachusetts. Color coded version (right) by Henry W. Art shows lot types more clearly.

James Henry Coffin, born in Williamstown in 1806, held a number of teaching positions, including one at Williams College from 1840–46. During this time, he created the first map of the early settlement of Williamstown, showing how land was partitioned into categories that were equitably allocated among the settlers of the previous century. Coffin used the detailed written information recorded in the town’s Proprietors Book dating back to 1750. The color-coded version of Coffin’s map shows how land was distributed to these settlers according to the medieval European open-field system. House lots were clustered together along Main Street. Using a lottery system to ensure fairness, each proprietor (landowner) was allocated a series of portions (or “lots”) containing good farming land, lesser farming land, freshwater marshes, and various woodlands.

Recovering Place: Reflecting on Stone Hill

By Mark C. Taylor

An illustrated book chronicling the land art and sculptures created by Mark C. Taylor at his home in the Berkshire hills, echoing themes found in the exhibition. Supported in part by Herbert A. Allen, Jr. and the Clark Art Institute and published by Columbia University Press. Call the Museum Store at 413 458 0520 to order.